AbstractObjectiveSeveral abbreviated versions of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) have been developed and are widely used in clinical settings. In this study, we provide evidence supporting the use of abbreviated versions of AUDIT by comparing the utility of various abbreviated versions and determining cut-off values for the population of South Korea.

MethodsData were obtained from the 4th to 6th Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. After calculating the whole AUDIT score, we applied the cut-off value of at-risk drinking proposed by the World Health Organization and divided the study sample into normal and at-risk drinking groups. Receiver operating characteristic curves were drawn for AUDIT-3rd question (Q3) alone, AUDIT-quantity and frequency (QF), AUDIT-consumption (C), AUDIT-4, and AUDIT-primary clinic (PC), and optimal cut-off values were obtained for each group.

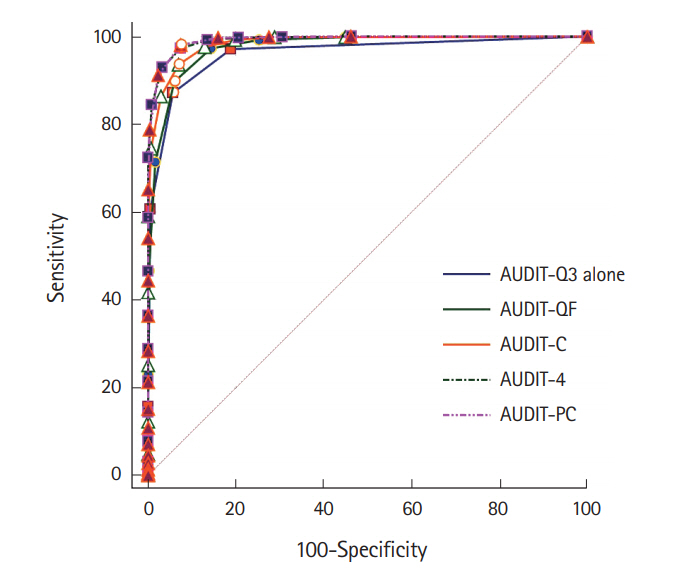

ResultsA total of 46,450 subjects were analyzed. The at-risk drinking group comprised 29.2% of all subjects. The area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of the abbreviated versions of AUDIT increased from 0.954 to 0.991 as the number of questions increased from one to four. The differences in AUROC between the abbreviated versions of AUDIT were statistically significant. The most appropriate cut-off values for AUDIT-Q3 alone, AUDIT-QF, AUDIT-C, AUDIT-4, and AUDIT-PC for adults over age 19 were 2, 4, 5, 6, and 4 points, respectively.

INTRODUCTIONIt is necessary to understand current patterns of alcohol consumption before setting up regulatory policies. Alcohol consumption patterns are analyzed through national health indicators in the United States and other countries [1]. The South Korean government conducts a nationwide survey, the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), that includes the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) developed by the World Health Organization [2]. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has proposed several clinical situations as key opportunities to screen for at-risk drinking, including in emergency departments or urgent care centers, and when prescribing a medication that interacts with alcohol [3]. The emergency department is an important clinical setting for screening for at-risk drinking and conducting brief interventions, and many studies have shown that brief interventions in the emergency department focusing on alcohol consumption are effective [4-7]. However, it is often difficult to administer the full AUDIT questionnaire, which consists of 10 questions, in the emergency department, where urgent care is conducted simultaneously. A substantial amount of research on the abbreviated versions of AUDIT has been performed, and various tests and cut-off values have been presented [8-15]. While these tests are internationally available, they must take into account each countryŌĆÖs culture and other characteristics. Specifically, cut-off values must be determined based on research findings and expert opinion. Research conducted to date on the AUDIT in South Korea is sparse and has been limited to males [15]. In the present study, we provide evidence supporting the use of abbreviated versions of AUDIT in South Korea by comparing the utility of various abbreviated versions in a national sample and determining appropriate cut-off values.

METHODSStudy designWe obtained the study data from the KNHANES website and analyzed alcohol-related items. This study, peformed using national public health data, was exempt from informed consent. The study was approved by the hospitalŌĆÖs institutional review board (EMCIRB 18-13).

Study populationAnalyses were conducted on 46,450 individuals at least 19 years of age using data from the 4th to 6th KNHANES, conducted between 2007 and 2015.

Study protocolData were obtained by requesting raw data through the KNHANES homepage of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [16]. The extraction framework of the KNHANES uses the most recent population and housing census data available at the time of sample design. The sample design of the KNHANES IV (2007 to 2009) used 2005 population and housing census data. In the case of the KNHANES V (2010 to 2012), the population and housing census data were aged at the time of the design of the survey, and the resident population and apartment complex survey data were used as the extraction framework. The KNHANES VI (2013 to 2015) stratified the extraction framework based on provinces, cities, towns and villages, as well as housing types. The KNHANES included a common variable survey, a health questionnaire, a screening survey, and a nutrition survey. Socioeconomic location indicators were also collected, and weights for the selected subjects in the study area were calculated. The health questionnaire included 12 alcohol-related items: 10 questions based on the AUDIT and 2 questions about drinking experience and expert consultation. The alcohol-related questions did not vary between survey waves, with the exception of the second year of KNHANES IV (2014). For this reason, data from the KNHANES IV-2 (2014) were excluded from analysis (Fig. 1).

We summarized the abbreviated versions of AUDIT to be analyzed based on a literature review [8-15]. After obtaining the whole AUDIT score, we applied the cut-off values (8 for males, 7 for females and 7 for elderly over 65 years old) of at-risk drinking proposed by the World Health Organization and divided survey respondents into normal and at-risk drinking groups [17]. At-risk drinking is defined as drinking that increases the risk of alcohol-related problems. The at-risk drinking group was stratified into three groups (male, female, and elderly).

Statistical analysisReceiver operating characteristic curves were drawn for AUDIT-3rd question (Q3) alone, AUDIT-quantity and frequency (QF), AUDIT-consumption (C), AUDIT-4, and AUDIT-primary clinic (PC), and optimal cut-off values were obtained for each group. The KNHANES was designed to extract representative samples for the population over 1 year of age living in South Korea. The survey was conducted using two-stage stratified cluster sampling, a complex sampling method requiring that strata, cluster, and sample weight be taken into account in data analysis. However, in the present study we did not intend to measure national prevalence of at-risk drinking, and our analyses were conducted using simple random sampling methods. Area under receiver operating characteristic curves (AUROC) of previous abbreviated versions of AUDIT were obtained, and the difference between the areas was analyzed using the method of DeLong et al. [18] Analyses were conducted using MedCalc Statistical ver. 17.2 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org, 2017).

RESULTSBaseline characteristicsA total of 46,450 subjects were analyzed. 19,703 (42.4%) were male and 26,747 (56.7%) were female. The average age was 50.0 years. The at-risk drinking group comprised 29.2% of all subjects, and 51.7%, 17.6%, and 15.2% of the male, female, and elderly groups, respectively.

Comparison of outcomesSix abbreviated versions of AUDIT were analyzed, as shown in Table 1 [9,14,19-31]. The number of questions and the development process varied between versions. The AUROC of the abbreviated versions of AUDIT increased from 0.954 to 0.991 as the number of questions analyzed increased. The differences in AUROC between the abbreviated versions were statistically significant. For the Fast Alcohol Screening Test, the AUROC was not applied as a dichotomous test (Tables 2, 3, and Fig. 2).

The most appropriate cut-off values for the AUDIT-Q3 alone, AUDIT-QF, AUDIT-C, AUDIT-4 and AUDIT-PC for all adults over 19 years were 2, 4, 5, 6, and 4 points, respectively. In subgroup analyses, the most appropriate cut-off values were 2, 5, 6, 7, and 5 points for males; 2, 3, 5, 5, and 4 points for females; and 1, 3, 3, 5, and 4 points for elderly. Most cut-off values were higher in males than in females and lower in elderly individuals than in the non-elderly (Table 4).

DISCUSSIONTo validate the abbreviated versions of AUDIT and to propose appropriate cut-off values for South Korea, we used data from the KNHANES IV to VI excluding KNHANES VI-2 (2014). Diagnosis of at-risk drinking was based on the whole AUDIT score. AUROC, cut-off value, sensitivity, and specificity were obtained for each abbreviated version of AUDIT. In previous studies on AUDIT-C, the most widely used abbreviated version, the gold standards for at-risk drinking group were set as (1) whole AUDIT score [15,31,32], (2) 4 standard drinks in a day or 14 standards drinks in a week for men, 3 standard drinks in a day or 7 standards drinks in a week for women and elderly [11-13], (3) pure alcohol consumption per week of 280 g for men or 168 g for women [9], and (4) daily alcohol consumption of 40 grams for men or 20 g for women [10]. In our study, the whole AUDIT score was used as a gold standard for at-risk drinking. The AUDIT is the most widely used alcohol screening test in the world, and its reliability has been demonstrated in various studies. The cut-off values of AUDIT for at-risk drinking proposed by the World Health Organization are 8 points for men, 7 points for women and 7 points for elderly people. To examine the previous studies of AUDIT cut-off values for at-risk drinking or problem drinking in South Korea, Kim et al. [33] conducted a study in which individuals were classified as ŌĆśnormal,ŌĆÖ ŌĆśphysical problem drinking,ŌĆÖ ŌĆśalcohol abuse,ŌĆÖ or ŌĆśalcohol dependence.ŌĆÖ The gold standard was a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition questionnaire combined with a blood test. In this study, the term ŌĆśphysical problem drinkingŌĆÖ refers to ŌĆśno mental-social problems,ŌĆÖ i.e., abnormal blood tests, but not alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence. As a result, a cut-off value of 12 points on the AUDIT was proposed for physical problem drinking in South Korea. In another study from South Korea [34], the AUDIT cut-off values for at-risk drinkers were 10 in males, 6 in females, and 8 in all subjects combined, using a simple 4 questions self test for alcohol screening, CAGE (cut down, annoyed, guilty, eye-opener) 1 point as the gold standard. It should be noted that accepting US standards without modification may be problematic. However, in previous studies of AUDIT cut-off values in Korea [33,34], different definitions were applied for problem drinking or at-risk drinking. As it would be unreasonable to apply the results obtained by that method as is, we instead chose to apply internationally accepted standards [17].

In our study, the AUROC increased to a statistically significant level as the number of items was increased from one to four. There was no difference in the AUROC between the four-item AUDIT-4 and the AUDIT-PC. In terms of the AUROC, as the number of items increases, the test becomes more accurate. However, in order to maximize simplicity and brevity of testing, using fewer items would be advantageous. From this perspective, AUDIT-QF or AUDIT-C would be preferred as abbreviated versions of AUDIT.

In this study, optimal cut-off values were obtained for all adults over 19 years of age and for three subgroups. The cut-off values were 2, 2, 2, and 1 for AUDIT-Q3 alone; 4, 5, 3, and 3 for AUDIT-QF; 5, 6, 5, and 3 for AUDIT-C; 6, 7, 5, and 5 for AUDIT-4; and 4, 5, 4, and 4 for AUDIT-PC in all adults, males, females and elderly individuals, respectively. Most cut-off values were higher in males than in females and lower in elderly compared to non-elderly individuals. Appropriate cut-off values for screening for at-risk drinking have been presented in several studies conducted in various countries. In a Korean validation study of AUDIT-C for screening for problem drinking [15], the AUDIT-C cut-off value for risk drinking in adult males was 8, based on whole AUDIT scores ranging up to 12. In contrast, in a study conducted in Spain in 2002 [9], the proposed AUDIT-C cut-off values were 5 for males and 4 for females based on alcohol consumption per week of 280 g for men and 168 g for women. In a study conducted in Taiwan in 2008 [10], the determined cut-off values for AUDIT-C were 4 for females and 5 for males, based on 40 g per serving for men and 20 g per serving for women. In several studies conducted in the United States, the AUDIT-C cut-off value for problem drinking was in the range of 4 to 5 for men and 2 to 3 for women, with results varying slightly between studies [8,11,12]. Cut-off values of abbreviated versions of AUDIT found in other countries are 1 to 2 for AUDIT-Q3 alone, 3 to 4 for AUDIT-QF, 4 to 6 for AUDIT-C for males and 2 to 5 for females, 5 to 7 for AUDIT-4, and 4 to 5 for AUDIT-PC [8-12,14,15,17,24,30,31,35,36], which are similar to our results. In our study, we propose appropriate cut-off values by analyzing not only gender but also the elderly population over 65 years of age. In addition, using KNHANES as a source of representative national health data, our results are generalizable to the entire country. The primary limitation of our study was that the exact amount or frequency of alcohol consumption was unknown, because alcohol-related items in KNHANES mainly consist of AUDIT questions. Using the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism criteria for at-risk drinking (4 standard drinks in a day or 14 standards drinks in a week for men, 3 standard drinks in a day or 7 standards drinks in a week for women and elderly) as a gold standard, the results of our study will be more reliable and easily compared to other studies.

In summary, using the KNHANES, the sensitivity, specificity, AUROC and appropriate cut-off value of abbreviated versions of AUDIT for Korean adults are proposed in this study. The AUROC increased to a statistically significant level as the number of items analyzed increased from one to four. The cut-off values found for the abbreviated versions of AUDIT were similar to those found in other countries. By understanding current patterns of alcohol consumption and establishing cut-off values for Korea, we expect the abbreviated versions of AUDIT to play an important role as a valid screening test.

REFERENCES1. Pleis JR, Ward BW, Lucas JW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2009. Vital Health Stat 2010; 10:1-207.

2. Ministry of Health and Welfare; Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea health statistics 2009: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANESIV-3). Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2010.

3. Willenbring ML, Massey SH, Gardner MB. Helping patients who drink too much: an evidence-based guide for primary care clinicians. Am Fam Physician 2009; 80:44-50.

4. Patton R, Green G. Alcohol identification and intervention in English emergency departments. Emerg Med J 2017; May; 8; https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2016-206467.

5. Duroy D, Boutron I, Baron G, Ravaud P, Estellat C, Lejoyeux M. Impact of a computer-assisted Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment on reducing alcohol consumption among patients with hazardous drinking disorder in hospital emergency departments. The randomized BREVALCO trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016; 165:236-44.

6. van Loon M, van Gaalen AC, van der Linden MC, Hagestein-De Bruijn C. Evaluation of screening and brief intervention for hazardous alcohol use integrated into clinical practice in an inner-city emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med 2017; 24:224-9.

7. Walton MA, Chermack ST, Blow FC, et al. Components of brief alcohol interventions for youth in the emergency department. Subst Abus 2015; 36:339-49.

8. Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:821-9.

9. Gual A, Segura L, Contel M, Heather N, Colom J. Audit-3 and audit-4: effectiveness of two short forms of the alcohol use disorders identification test. Alcohol Alcohol 2002; 37:591-6.

10. Wu SI, Huang HC, Liu SI, et al. Validation and comparison of alcohol-screening instruments for identifying hazardous drinking in hospitalized patients in Taiwan. Alcohol Alcohol 2008; 43:577-82.

11. Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007; 31:1208-17.

12. Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Zhou Y. Effectiveness of the derived Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the US general population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005; 29:844-54.

13. Burns E, Gray R, Smith LA. Brief screening questionnaires to identify problem drinking during pregnancy: a systematic review. Addiction 2010; 105:601-14.

14. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158:1789-95.

15. Seong JH, Lee CH, Do HJ, et al. Performance of the AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C) and AUDIT-K question 3 alone in screening for problem drinking. Korean J Fam Med 2009; 30:695-702.

16. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 4th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [Internet]. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009 [cited 2017 Jan 20]. Available from: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/.

17. World Health Organization. The alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary care. 2nd. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

18. DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988; 44:837-45.

19. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: II. Addiction 1993; 88:791-804.

20. Sanchez-Craig M, Wilkinson DA, Davila R. Empirically based guidelines for moderate drinking: 1-year results from three studies with problem drinkers. Am J Public Health 1995; 85:823-8.

21. Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S. Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: a national survey of students at 140 campuses. JAMA 1994; 272:1672-7.

23. Seppa K, Lepisto J, Sillanaukee P. Five-shot questionnaire on heavy drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1998; 22:1788-91.

24. Aalto M, Tuunanen M, Sillanaukee P, Seppa K. Effectiveness of structured questionnaires for screening heavy drinking in middle-aged women. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006; 30:1884-8.

25. Buchsbaum DG, Welsh J, Buchanan RG, Elswick RK Jr. Screening for drinking problems by patient self-report. Even ŌĆśsafeŌĆÖ levels may indicate a problem. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:104-8.

26. Cyr MG, Wartman SA. The effectiveness of routine screening questions in the detection of alcoholism. JAMA 1988; 259:51-4.

27. Moulton A, Cyr M, Osullivan PS, Desai T. Screening for alcoholism in women in an internal medicine practice. Clin Res 1990; 38:A700.

28. Moran MB, Naughton BJ, Hughes SL. Screening elderly veterans for alcoholism. J Gen Intern Med 1990; 5:361-4.

29. Schorling JB, Willems JP, Klas PT. Identifying problem drinkers: lack of sensitivity of the two-question drinking test. Am J Med 1995; 98:232-6.

30. Piccinelli M, Tessari E, Bortolomasi M, et al. Efficacy of the alcohol use disorders identification test as a screening tool for hazardous alcohol intake and related disorders in primary care: a validity study. BMJ 1997; 314:420-4.

31. Hodgson R, Alwyn T, John B, Thom B, Smith A. The FAST alcohol screening test. Alcohol Alcohol 2002; 37:61-6.

32. Kaarne T, Aalto M, Kuokkanen M, Seppa K. AUDIT-C, AUDIT-3 and AUDIT-QF in screening risky drinking among Finnish occupational health-care patients. Drug Alcohol Rev 2010; 29:563-7.

33. Kim JS, Oh MK, Park BK, Lee MK, Kim GJ. Screening criteria of alcoholism by alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in Korea. J Korean Acad Fam Med 1999; 20:1152-9.

34. Joe KH, Chai SH, Park A, Lee HK, Shin IH, Min SH. Optimum cut-off score for screening of hazardous drinking using the Korean version of alcohol use disorder identification test (AUDIT-K). J Korean Acad Addict Psychiatry 2009; 13:34-40.

Fig.┬Ā1.Profile of study population. KNHANES, Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Fig.┬Ā2.Receiver operating characteristic curves of abbreviated versions of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT). Q3, 3rd question; QF, quantity and frequency; C, consumption; PC, primary clinic.

Table┬Ā1.Abbreviated versions of AUDIT

Table┬Ā2.AUROCs of abbreviated versions of the AUDIT

Table┬Ā3.Pairwise comparisons of area under receiver operating curve of abbreviated versions of AUDIT Table┬Ā4.Cut-off values, sensitivities, and specificities of abbreviated versions of the AUDIT |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||