Dear Editor,

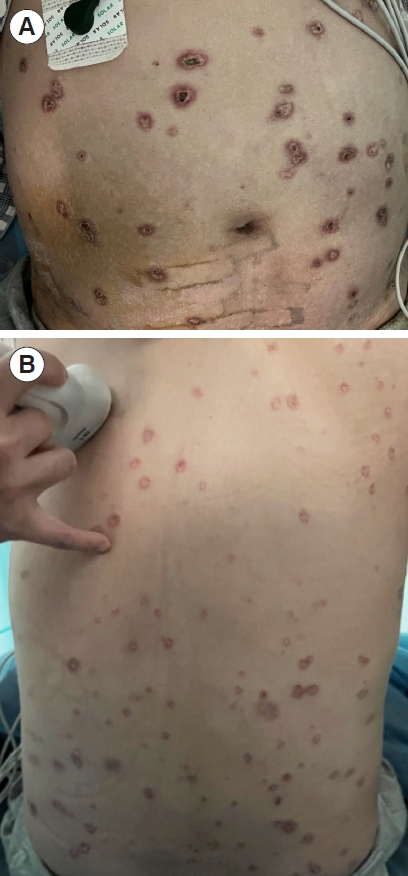

We would like to share the interesting case of a 38-year-old woman who presented to the emergency department of an outside hospital with a rash accompanied by severe abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fever. The rash had been intermittent for 2 years, was located over the neck, trunk, arms, and legs, and was not accompanied by tenderness or itching. Skin biopsy and pathological examination performed 1 year prior showed partial epidermal atrophy, local fibrous hyperplasia and hyaline degeneration of the dermis, and multiple mucus deposits between surrounding collagen, at which point a diagnosis of Degos disease was made. The patient experienced prominent recurrence of the rash in the preceding 20 days. The patient denied cough, sputum, headache, paralysis, or paresthesia. Based on her history and test results, a diagnosis of malignant atrophic papulosis (MAP) and acute peritonitis with ascites was made at the local hospital. After receiving ceftriaxone and glucocorticoids, her condition did not improve significantly. She was transferred to our emergency department. The patient was conscious with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15 and her vital signs were temperature 38.9 °C, heart rate 137 beats/ min, respiratory rate 33 breaths/min, blood pressure 107/73 mmHg, and pulse oximetry 99% on room air. Physical examination showed generalized, painless, nonpruritic, ring-shaped pigmented plaques, the majority of which were crusted over, particularly the scattered abdominal lesions (Fig. 1).

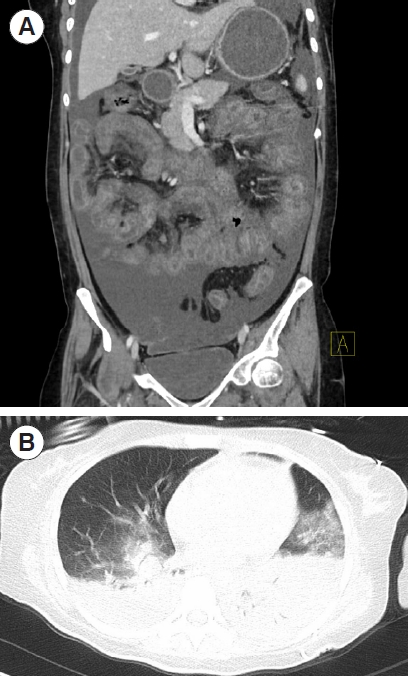

The patient’s white blood cell count was elevated (11.35×109/L), as was procalcitonin (0.51 ng/mL). Chest and abdominal computed tomography revealed a thickened intestinal wall, swollen mesentery, ascites, bilateral pleural effusion, and diffuse bilateral pulmonary consolidation (Fig. 2). The patient was COVID-19 negative. A peripheral smear and culture of the patient’s abdominal fluid revealed increased mesothelial cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, without tumor cells. Blood culture results from the outside hospital were positive for Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus avium (received on the 1st day after admision).

The patient’s history, physical examination, and blood and culture results suggested a diagnosis of MAP and sepsis from intestinal inflammation with ascites and pneumonia. Methylprednisolone (40 mg/day), heparin (5,000 U/day), and imipenem were immediately initiated. The gastrointestinal (GI) team found no signs of intestinal perforation or necrosis and thus surgery was not recommended. Immunotherapy against C5 (e.g., eculizumab) was refused by the patient and her family. She clinically deteriorated, developing respiratory failure and shock on treatment day 2. In compliance with her family’s wishes, the patient was discharged home without exploratory laparotomy. She expired 2 days later.

This study is in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Human Ethical Committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University (No. 2,019,201). Written informed consent for publication of the research details and clinical images was obtained from the patient’s parents.

Degos disease is a rare, multisystem, immune-related vasculopathy with a cutaneous form (benign atrophic papulosis) and a systemic variant, MAP [1]. Approximately 200 cases have been reported in the literature [2]. Lesions may appear at different stages in various locations, with the trunk being the most common. The GI tract and the central nervous system are most often affected in MAP, though there are reports of possible involvement of other organs, such as the respiratory system and the eyes [3]. Common causes of death include GI perforation leading to hemorrhage and cerebrovascular accidents [3,4]. The underlying mechanisms of the systemic manifestations of Degos disease are not well understood [5]. One hypothesis is that ischemia-induced proliferation and swelling of endothelial cells with dysregulated C5–9 membrane attack complexes may be responsible [6]. The diagnosis of atrophic papulosis is made clinically and supported by histologic findings [3]. The median survival time of MAP is 2 to 3 years; the 5-year survival rate is <50% [7]. Intestinal perforations are uncommon in MAP (up to 2.1%) [8]. Almost 60% of cases of death are due to the most common complications, which are peritonitis caused by intestinal perforation and cerebral infarction [9].

In this patient, the diagnosis and treatment of sepsis were delayed given her initial presentation at an outside hospital. We lost the opportunity to administer antibiotics in a timely manner in line with the surviving sepsis campaign [10]. Notably, there is no proven therapy against MAP. Immunosuppressants, anticoagulants, and antiplatelet medications are the first-line therapeutic approach in newly diagnosed patients. Eculizumab is a salvage therapy in critically ill MAP patients [6], but there is questionable mortality benefit in patients with perforation [9]. Our patient’s sporadic use of prednisone limited steroidal efficacy against vascular inflammation. It is likely that our patient developed systemic symptoms from destabilized gastrointestinal lesions, leading to peritonitis and sepsis, i.e., life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection [10]. Our patient did not undergo laparotomy. Numerous reports have documented patient death from MAP despite surgical interventions [9,11,12]. Therefore, whether surgery is a definitive, efficacious treatment for MAP warrants further exploration.

In conclusion, the prognosis for systemic MAP is poor, especially when the gastrointestinal system is involved. No therapy with substantial mortality benefit has been established. Early identification and appropriate sepsis management remain the best practice. Timely medical treatment of MAP and its complications is a significant challenge. Emergency physicians and dermatologists must remain vigilant for serious complications when treating Degos disease, particularly sepsis.