Effectiveness and safety of electrical cardioversion for acute-onset atrial fibrillation in the emergency department: a real-world 10-year single center experience

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Despite limited evidence, electrical cardioversion of acute-onset atrial fibrillation (AAF) is widely performed in the emergency department (ED). The aim of this study was to describe the effectiveness and safety of electrical cardioversion of AAF performed by emergency physicians in the ED.

Methods

All episodes of AAF electrically cardioverted in the ED were retrieved from the database for a 10-year period. Most patients not already receiving anticoagulants were given enoxaparin before the procedure (259/419). Procedural complications were recorded, and the patients were followed-up for 30 days for cardiovascular and hemorrhagic complications.

Results

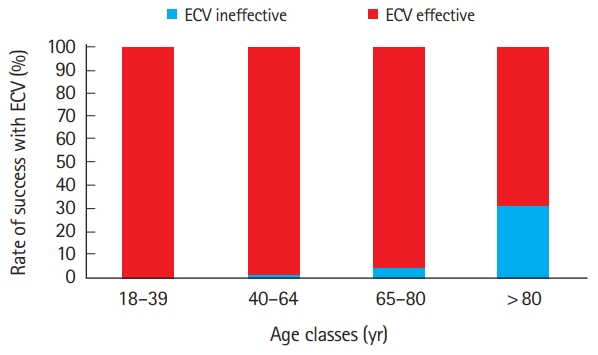

Four hundred nineteen eligible cases were identified; men represented 69%, and mean age was 61±13 years. The procedure was effective in 403 cases (96.2%; 95.4% in women, 96.5% in men), with considerable differences with respect to the age of the patients, the procedure being effective in 100% of patients aged 18 to 39 and only 68.8% in those >80 years. New ED visits (33/419) were identified within 30 days (31 due to atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter recurrence, 1 due to iatrogenic hypokalemia, 1 due to hypertensive emergency). No strokes, major bleeding, life-threatening arrhythmias or peripheral thromboembolism were recorded. Nine small and mild skin burns were observed.

Conclusion

Electrical cardioversion is an effective and safe procedure in the vast majority of patients, albeit less effective in patients aged >80 years. It appears reasonable to avoid anticoagulation in low-risk patients with AAF and administer peri-procedural heparin to all remaining patients. Long-term anticoagulation should be planned on an individual basis, after assessment of thromboembolic and hemorrhagic risk.

INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, and needs early and appropriate management, since it is associated with enhanced cardiovascular mortality and morbidity burden. Although it has now been clearly demonstrated that AF is characterized by a progressively increasing incidence in parallel with population ageing [1], some less frequent forms may be observed in young people and even in highly trained athletes [2].

In the last two decades, two main strategies for the management of AF have been endorsed and widely accepted: 1) rate control (achieving acceptable heart rate with no attempts to restore sinus rhythm and employing an associated anticoagulant therapy in accordance with the thromboembolic and bleeding risks); 2) rhythm control (one or more attempts to restore sinus rhythm) [3]. The decision as to whether it is appropriate to obtain and maintain sinus rhythm should be made on a personalized basis, mainly depending on symptoms, type of AF, presence of structural heart disease, age or comorbidities, and need for anticoagulation. The severity of AF-related symptoms should ultimately guide the final decision.

There is still considerable variation in emergency department (ED) management of recent-onset AF between several world regions, mostly represented by different choices about use of rate versus rhythm control, different choice of drugs, and widely variable use of electrical cardioversion (ECV) [4]. Generally, although clear evidence in support of a real clinical advantage is currently lacking, the popularity of the rhythm control strategy has considerably increased in EDs, with the aim of reducing hospitalizations and health care costs [5-8].

As concerns acute management strategies, all the main guidelines do not distinguish between AF and atrial flutter (AFl), due to their rather similar thromboembolic risk [3,9,10]. It is commonly assumed that cardioversion may be associated with an inherent risk of stroke in non-anticoagulated patients, which can be substantially reduced by anticoagulation administration [11]. This concept has led some authors to suggest immediate initiation of anticoagulation in all patients scheduled for cardioversion [12,13], despite limited evidence and controversial guidelines on this issue [3,9,10].

Although only a limited number of studies on it has been published, ECV has been proven to be a safe procedure when performed in the ED [14-20], and has become a universally accepted and widely performed procedure, especially when using biphasic rather than monophasic external defibrillators [21,22]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe, in a real-world scenario, the effectiveness and safety of ECV of acute-onset atrial fibrillation (AAF) and acute-onset atrial flutter (AAFl) performed by emergency physicians in the ED.

METHODS

In this retrospective and observational study, all episodes of AAF (both first-diagnosed AF and paroxysmal-AF) and AAFl for which ECV was performed during ED stay were retrieved from the electronic hospital database for a period of 3,653 days (between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2016). The University Hospital of Parma, an 1,100-bed general and teaching hospital serving a population of nearly 340,000 inhabitants, is the only hospital in our area, thus enabling the enrollment and accurate follow-up of all patients living in the hospital area. The healthcare facility is also a level 2 trauma center, and a reference hospital for the management of patients with stroke and acute myocardial infarction. Only cases with an onset of AF within 48 hours from the ED visit were included. When the onset of arrhythmia could not be precisely defined, the case was excluded. All clinical records were separately examined by two authors (LB and GC) to verify and exclude inaccurate recording.

According to local protocols, ECV is performed in the local ED by using a Lifepak 12 (Physio Control, Redmond, WA, USA) monitor-defibrillator, after sedation and analgesia with fentanyl (1 μg/kg of body weight) and midazolam (0.10–0.20 mg/kg of body weight, based on clinical response). Once reasonable sedation has been achieved, biphasic direct current shock is performed, generally starting at 100 to 150 joules (based on the weight and physical structure of the patient, as well as the type of arrhythmia; AF vs. AFl). When necessary, a maximum of two additional shocks at increasing energy are administered. After the procedure is finalized, flumazenil (0.5–1 mg) is administrated for accelerating awakening. The procedure is considered as successful when sinus rhythm is restored and maintained until ED discharge (generally after 3–4 hours, when acceptable wakefulness is restored).

Most patients received enoxaparin at 1 mg/kg of body weight before the procedure (259/419, 61.8%), unless previously treated with oral anticoagulant therapy (OAT) (81/419, 19.3%), while long term OAT therapy was administered on an individual basis, based on CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores. The choice of the anticoagulant treatment is discussed in detail in a following section of this article. Procedural complications were accurately recorded, and information on patients with further ED admissions within 30 days after previous discharge was carefully analyzed, especially for obtaining data on thromboembolic events and cardiovascular and hemorrhagic complications leading to the second visit. Moreover, we subdivided the patients already on anticoagulants at ED presentation, and the patients for whom an anticoagulant therapy was prescribed at discharge from the ED. The whole sample was furthermore subdivided according the CHA2DS2-VASc score.

Due to the retrospective design of this study, which also entailed complete anonymization of patient data, ethical committee approval was unnecessary, in accordance with local policy. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki under the terms of relevant local legislation.

RESULTS

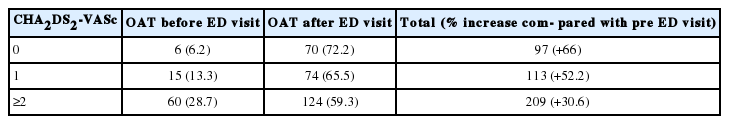

A total number of 419 eligible patients with ECV for AAF and AAFl were identified. Of these, 115 were classified as first AF episode, while the remaining patients were classified as recurrent cases. Men constituted nearly two-thirds of the sample (289/419, 69%). Mean age was 61.1±13.1 years (median, 63 years). According to thromboembolic risk, as established through the CHA2DS2-VASc score, we found that 6 of 97 (6.2%) patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 were already on anticoagulants at presentation. In contrast, 15 of 113 (13,3%) patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 and 60 of 209 (28,7%) of patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2 were on anticoagulants at presentation.

At discharge from the ED, excluding all patients already on anticoagulants for whom this therapy was maintained, 70 additional patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0, 74 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1, and 124 patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2 were treated with anticoagulants (Table 1). The procedure was effective in restoring sinus rhythm in 403 cases (96.2%). Despite the effectiveness of ECV being very similar in both genders (95.4% in women versus 96.5% in men), we observed a marked difference in the effectiveness of the procedure in accordance with patient age, as presented in Fig. 1. More specifically, ECV was effective in all (100%) patients aged between 18 and 39 years; the efficiency then gradually decreased in parallel with advancing age (the effectiveness was 97.3±1.1% in patients aged 65 to 80 years). Interestingly, in four out of five unsuccessful outcomes recorded in patients aged >80 years, ECV had been performed as an emergency procedure, due to hemodynamic instability and presence of severe co-morbidities.

Patients subdivided according to their CHA2DS2-VASc score and their anticoagulant therapy status, before and after ED visit and electrical cardioversion

Rate of success of electrical cardioversion (ECV) of atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter, according to age groups.

A total number of 33/419 (7.9%) new ED visits were identified within 30 days from the first ED discharge. Thirty-one of these cases (93.9%) were due to AF/AFl recurrence, one (3%) due to iatrogenic hypokalemia, and the remaining (3%) due to hypertensive emergency. No episodes of stroke, major bleeding, life-threatening arrhythmias or peripheral thromboembolism were recorded. The AF/AFl recurrences were managed on second ED visits, as follows: 14 cases (43%) with successful pharmacological cardioversion; 5 cases (15%) with successful ECV; 3 cases (9%) with spontaneous restoration of sinus rhythm during ED stay; and 9 cases (27%) were not cardioverted in accordance with clinical judgement and/or patient decision.

In the entire patient sample, only 9 skin burns of first or second degree were observed, always limited to the pads surface. All the episodes occurred in a limited temporal window (approximately 3 months). When analyzing this problem, we found that the complication was due to single batch of faulty pads.

DISCUSSION

The 2006 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/European Society of Cardiology (ACC/AHA/ESC) guidelines on AF recommended that cardioversion could be performed when clinically appropriate, without delay for prior initiation of anticoagulation in patients with AF of <48-hour duration (level of evidence: C), and that the choice of administering anticoagulant therapy during the 48 hours after the onset of AF should depend on individual risk of thromboembolism (level of evidence: C) [23].

To date, an important and almost unresolved question remains about the utility of cardioversion in patients with AAF (<48 hours) and no indication for long-term anticoagulation; although relevant advice can be found in the available guidelines, some doubts persist. The Canadian guidelines recommend anticoagulation with intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) before cardioversion only in selected categories of high-risk patients (e.g., with mechanical valve, rheumatic valve disease, recent stroke, or transient ischemic attack) [9]. According to the ACC/AHA guidelines, it seems reasonable to administer heparin (intravenous bolus of UFH followed by infusion, or LMWH) or direct oral anticoagulants [10]. The ESC guidelines recommend using heparin (intravenous UFH bolus followed by infusion, or weight-adjusted therapeutic dose LMWH) before emergency cardioversion [3]. In patients with low risk of stroke, the ACC/AHA and ESC guidelines both recommend peri-procedural administration of heparin, while the Canadian guidelines advise against anticoagulation except in high-risk patients, in whom cardioversion should be delayed until after 3 weeks of anticoagulation. Since no randomized clinical trials have been published about the efficacy of peri-procedural heparin administration, the recommendations of the three available guidelines for hemodynamically stable patients with AAF are only based on observational studies and/or personal opinions.

Due to the lack of strong indications for anticoagulation in AF episodes lasting for <48 hours [24], the general long-term strategy in our local ED has been to cardiovert these episodes of AF, with no administration of post-procedural OAT. Only after 2010, when the new ESC guidelines recommended perioperative and long-term anticoagulation in patients with risk factors for stroke [25], was the peri-procedural management of ECV for AAF changed. However, the widespread implementation of this novel approach has been considerably slow, mainly due to weak evidence, consisting of small retrospective cardioversion studies, supporting the recommendation. This explains why up to 20% of our study population did not receive peri-procedural anticoagulation.

The FinCV study (the largest ever published on this topic) reported 38 definite thromboembolic events over 7,660 cardioversions (0.7%), within the 30-day follow-up [26]. In this study, which was retrospective and included nearly 12% pharmacological cardioversions, no patient received peri-procedural anticoagulant therapy, compared to 81.1% of patients in our series. One important additional finding of our study was that the medical contact with emergency physicians led to a re-evaluation of the thromboembolic and hemorrhagic risks, thus driving a substantial improvement in anticoagulant prescription. Even when considering the inherent limitations of retrospective studies, these facts could explain the different number of thromboembolic events between the two studies. Additional findings of our study substantially confirm those of the FinCV study. These include, a comparable success rate (96.2% vs 95.4%), a similar age of the patients (61±13 vs. 61±12 years), and a comparable male prevalence in gender distribution (68.9% vs. 63.7%).

In conclusion, our study shows that ECV is an effective and safe procedure when performed in the ED, provided a careful selection of patients has been made. Considering the limits related to the small number of patients, our data imply that the procedure tends to be less effective in older patients, in particular in those aged more than 80 years. In our sample, we did not observe any thromboembolic or hemorrhagic event. Therefore, we think that the safety of the procedure is largely dependent on the skills of the emergency physician in identifying patients with arrhythmia lasting less than 48 hours, and, even more importantly, in properly calculating the individual thrombo-embolic and hemorrhagic risks.

When a rhythm control strategy is advisable and shared with patients, we conclude that it may be reasonable to avoid anticoagulation in low-risk patients with AF lasting for <48 hours, and administer peri-procedural heparin (preferably LMWH, for practical reasons) to all the remaining patients. Long term anticoagulation should be planned on an individual basis, after accurate assessment of both the thromboembolic and hemorrhagic risk (using the CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores).

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Drs. Marco Brambilla and Marco Mignani of the University Hospital of Parma for the kind support in extracting data from the electronic databases of the institution.

References

Article information Continued

Notes

Capsule Summary

What is already known

An unresolved question remains about cardioversion in patients with acute-onset atrial fibrillation (<48 hours) and no indication for long-term anticoagulation. There is controversy and somewhat conflicting indications in the major guidelines.

What is new in the current study

When a rhythm control strategy is advisable and shared with patients, we conclude that it may be reasonable to avoid anticoagulation in low-risk patients with AF lasting <48 hours and to administer peri-procedural heparin (preferably low-molecular-weight heparin, for practical reasons) to all the remaining patients. Long term anticoagulation should be planned on an individual basis, after accurate assessment of both the thromboembolic and hemorrhagic risk (using the CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores).