Medical professionalism among emergency physicians in South Korea: a survey of perceptions and experiences of unprofessional behavior

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to analyze the current situation concerning professionalism among emergency physicians in South Korea by conducting a survey regarding their perceptions and experiences of unprofessional behavior.

Methods

In October 2018, the authors evaluated the responses to a questionnaire administered to 548 emergency physicians at 28 university hospitals. The participants described their perceptions and experiences concerning 45 unprofessional behaviors classified into the following five categories: patient care, communication with colleagues, professionalism at work, research, and violent behavior and abusive language. Furthermore, the responses were analyzed by position (resident vs. faculty). Descriptive statistics were generated on the general characteristics of the study participants. To compare differences in responses by position and sex, the chi-square and Fisher exact tests were performed.

Results

Of the 548 individuals invited to participate in this study, 253 responded (response rate, 46.2%). In 34 out of 45 questionnaires, more than half of participants reported having experienced unprofessional behavior despite their negative perceptions. Eleven perception questions and 38 experience questions for unprofessional behavior showed differences by position.

Conclusion

Most emergency physicians were well aware of what constituted unprofessional behavior; nevertheless, many had engaged in or observed such behavior.

INTRODUCTION

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education in the US recommends the inclusion of six essential competencies, including medical professionalism, in a medical curriculum [1]. In 2008, the Korea Institute of Medical Education and Evaluation emphasized the reinforcement of medical professionalism and social competence through a study on the common curriculum for residents in South Korea [2]. Subsequently, in 2014, the Korean Medical Association and the Ministry of Health and Welfare of South Korea issued a publication in which they described various future-oriented behaviors that physicians should exhibit. Physician roles were categorized into five areas: patient care, communication and cooperation, social accountability, professionalism, and education and research. The need to maintain a high level of work ethics based on professional job norms and self-regulation is emphasized in the area concerning professionalism, in which four competencies are further detailed: treatment based on ethics and autonomy, patient-physician relationships, self-regulation led by specialists, and professionalism and self-management [3]. A revised annual training curriculum for residents, announced by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in February 2019, identified additional competencies required for all residents; these were divided into the following eight categories: respect, ethics, patient safety, society, professionalism, excellence, communication, and teamwork [4]. The professionalism section among them includes professional integrity and self-management. Although the most important competencies may differ by field, the heads of various training hospitals officially announced that all residents should strive to master all competencies during training. However, despite these efforts by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of South Korea, training in medical professionalism has not been established in the curriculum of medical societies that train all medical residents in South Korea [4].

The 2019 Emergency Medicine Model Review Task Force also identified professionalism as a requirement for emergency medicine (EM) physicians, who often face disasters and other chaotic situations, in which they must make decisions almost instantly [5]. These situations can involve moral dilemmas like violence or ethical conflicts; therefore, professionalism is an essential competency for emergency physicians in particular. The 3rd and 4th year curricula for the residents of EM departments include: emergency medical treatment, ethics, patient-physician relationship, and other competencies [4]. However, these competencies are neither taught nor evaluated in the tests required for professional accreditation. Fortunately, a tool for evaluating medical professionalism is currently being developed, and studies examining professionalism among residents have been conducted [6-9].

Alternative and complementary education aimed at improving the physician’s understanding and management of unprofessional behaviors may be more useful than direct education targeting medical professionalism. Most physicians consider themselves professionals and are likely to perceive training in professionalism as unnecessary, or even insulting. Moreover, although it is difficult to quantify professional behavior, it is both possible and desirable to identify and quantify unprofessional behavior [10]. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the current perceptions and experiences of professionalism among EM residents and faculty members through a survey regarding unprofessional behaviors and to analyze the necessity of promoting medical professionalism based on the results.

METHODS

Study design, setting, and protocol

A total of 548 faculty members and residents from university hospital emergency departments in South Korea participated in the survey conducted from October to November, 2018. Twenty-eight universities were selected, including at least one from each metropolitan council. Survey Monkey (https://ko.surveymonkey.com/) was used to administer the survey. The first page of the survey stated the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation therein, the guaranteed anonymity of the participants, the confidentiality of the data, and the research purposes for which the data would be used. Only respondents who provided informed consent were included in the study. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital (No. 2018-08-004-004).

Survey questionnaire response categories and key outcomes

The questionnaire used in this paper was originally designed by Nagler et al. [11]. However, it was adapted for use in South Korea by five experts, who are professors with more than 10 years of educational experience in the college of medicine as EM specialists. The survey contains 45 questions in five categories: patient care (e.g., ‘explaining to patients the test results that the physician could not interpret,’ ‘not providing care, or providing discriminatory care based on the patient’s social background’); communication with colleagues (e.g., ‘not notifying senior staff regarding the medical mistakes made by colleagues’); professionalism at work (e.g., ‘attending a dinner or social party provided by a pharmaceutical/medical company,’ ‘surreptitiously leaving the emergency room while on duty because of personal issues’); research (e.g., ‘asking the author of a paper to name a person who did not contribute to it as a co-author,’ ‘manipulating research data to get the desired results’); and violent behavior and abusive language (e.g., ‘inflicting verbal or physical violence on students or juniors’). Each questionnaire item pertains to a behavior inconsistent with medical professionalism. Respondents were questioned regarding their perceptions and experiences of each type of unprofessional behavior. ‘Experiences’ comprise both observation of and engagement in the behavior. Questions about perceptions of unprofessional behaviors were accompanied by four answer options: ‘must not be done,’ ‘should not be done,’ ‘can be done depending on the circumstances,’ and ‘usually can be done.’ The responses ‘must not be done’ and ‘should not be done’ were considered indicative of a perception of unprofessional behavior. There were three answer options for questions about experiences of unprofessional behavior: ‘neither observed nor engaged in,’ ‘observed,’ and ‘engaged in.’ The responses were analyzed by position (resident vs. faculty).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated on the general characteristics of the study participants. To compare differences in responses by position and sex, the chi-square and Fisher exact tests were performed. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and the significance level was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 548 individuals invited to participate in this study, 253 responded (response rate, 46.2%). There were 212 men (83.8%) and 41 women (16.2%), and the median age of the participants was 34 years. Of the 253 participants, 117 held faculty positions (46.2%), and 136 were residents (53.8%) (Supplementary Table 1).

A majority of the responses to the questions about perceptions of unprofessional behavior were either ‘must not be done’ or ‘should not be done.’ Regarding questions about experiences, the responses were mostly either ‘observed’ or ‘engaged in.’ In 34 out of 45 questionnaires, more than half of participants reported having experienced unprofessional behavior despite their negative perceptions. The items with the highest level of agreement among respondents were ‘manipulating research data to get the desired results’ and ‘prescribing drugs to oneself, or prescribing antipsychotic drugs regardless of any other medical treatment’; 100% of respondents agreed that these actions constituted unprofessional behavior. The items with the lowest levels of respondent agreement were ‘dating a resident by a professor’ (perceived as unprofessional by 78.0%) and ‘experiencing pleasure when a patient decided not to receive emergency care’ (perceived as unprofessional by 77.6%). The highest rate of engagement in an unprofessional behavior was found for ‘experiencing pleasure when a patient decided not to receive emergency care’ (86.9%). Thus, respondents often engaged in this behavior despite the perception that it is unprofessional. The behaviors that respondents were least likely to cite having experience with were ‘touching a body part that is not necessary for diagnosis when examining a patient’ (0.0%), and ‘prescribing drugs to oneself or prescribing antipsychotic drugs regardless of any other medical treatment’ (0.5%). Respondents did not engage in these behaviors because they were perceived as unprofessional.

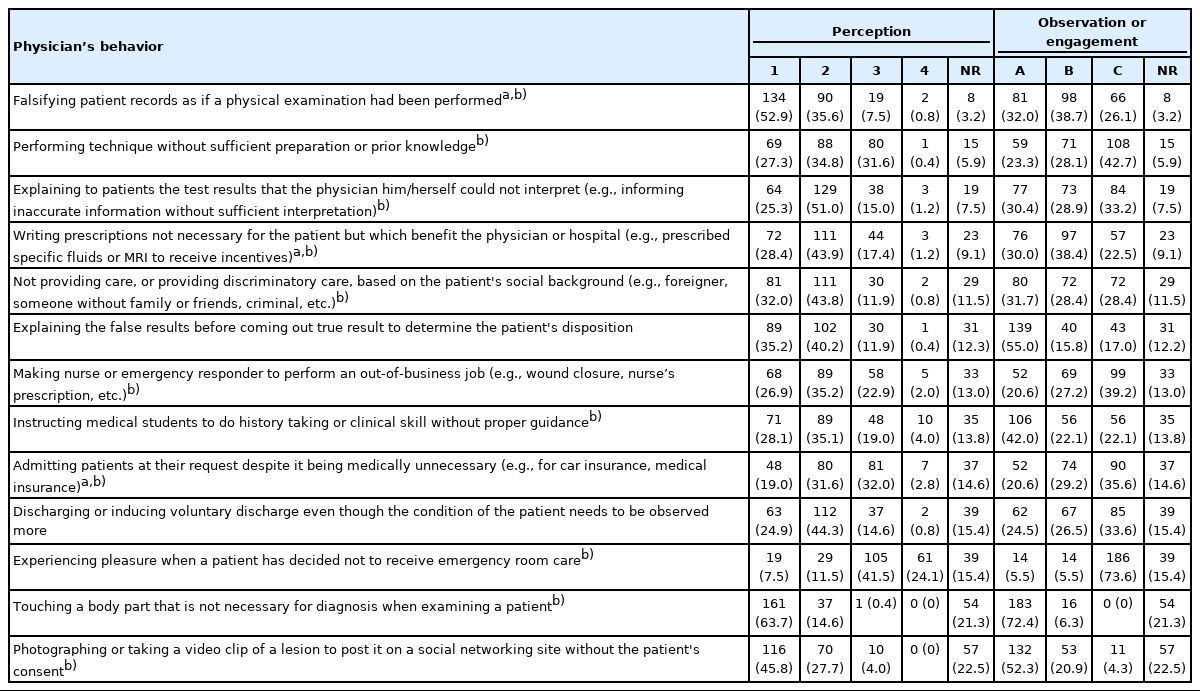

Regarding unprofessional behaviors related to patient care, most respondents perceived ‘touching a body part that is not necessary for diagnosis when examining a patient’ and ‘photographing or taking a video clip of a lesion to post it on a social networking site without the patient’s consent’ as unprofessional. Nevertheless, 32.6% of respondents stated that they had engaged in the latter behavior (Table 1).

Regarding unprofessional behaviors related to communication with colleagues, many respondents perceived ‘intentionally hiding information or transmitting false information so that a patient is sent to another hospital’ (98.4%) and ‘not reporting suspected child abuse or domestic violence to senior staff or relevant organizations’ (97.8%) as unprofessional. Nevertheless, 54.4% of respondents stated that they had experience with the former behavior (Table 2).

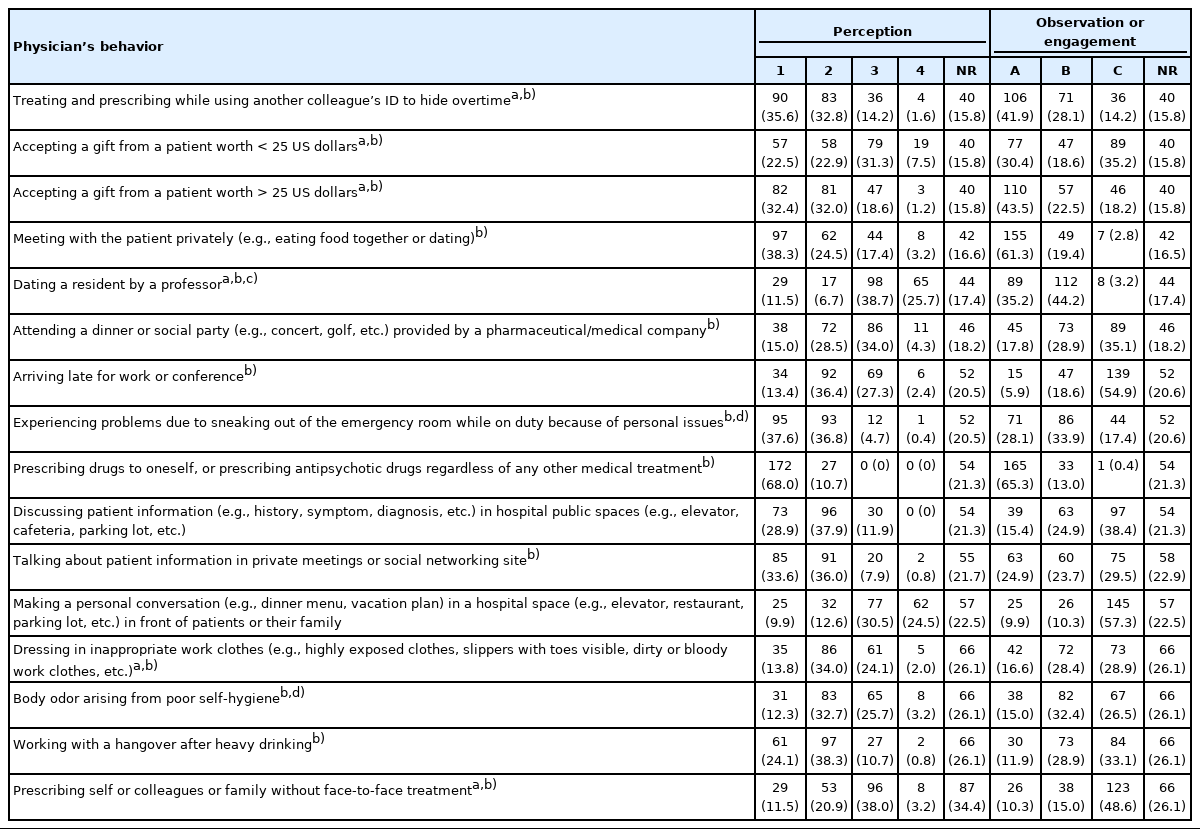

Regarding professionalism at work, most respondents perceived ‘prescribing drugs to oneself or prescribing antipsychotic drugs regardless of any other medical treatment’ and ‘surreptitiously leaving the emergency room while on duty because of personal issues’ as unprofessional behaviors. However, 78.0% of the respondents responded to the item ‘dating a resident by a professor’ with ‘can be done depending on the circumstances’ (Table 3).

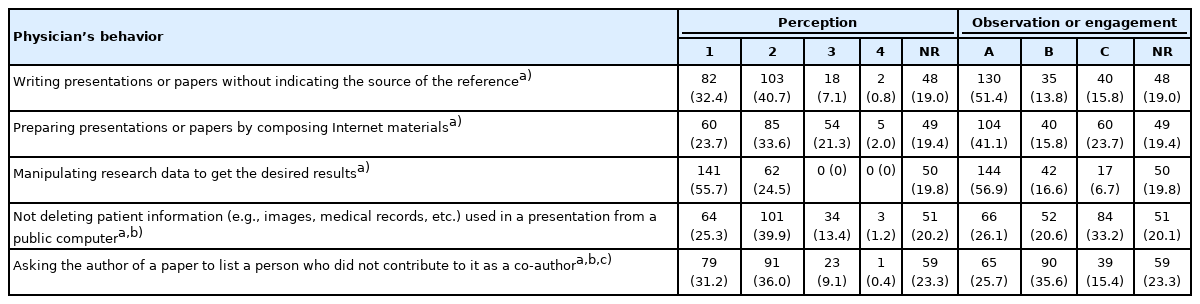

Regarding unprofessional behaviors related to research, most respondents agreed that ‘manipulating research data to get the desired results’ was unprofessional. In addition, a large percentage of respondents agreed that ‘asking the author of a paper to name a person who did not contribute to it as a co-author’ (87.6%) and ‘not deleting patient information used in a presentation from a public computer’ (81.7%) were unprofessional behaviors; nevertheless, engagement in these behaviors was reported by 66.5% and 67.3% of respondents, respectively (Table 4).

Regarding violent behavior and abusive language, a large percentage of respondents (99.5%) agreed that ‘ignoring or insulting the patients or their family in front of them’ was unprofessional behavior, despite which 77.4% of respondents agreed that they had done this themselves. ‘Blaming and gossiping about colleagues or other health professionals in front of students or junior physicians’ was also perceived as unprofessional behavior, but 81.9% of respondents reported having engaged in it (Table 5).

There were 11 perception questions and 38 experience questions for unprofessional behavior that showed differences by position (Tables 1-5 and Supplementary Tables 2, 3). Although 80.9% of the faculty members considered ‘writing prescriptions not necessary for the patient but benefit the physician or hospital’ was unprofessional, 30.0% indicated that they had engaged in this behavior. Similarly, 81.0% of the faculty members responded that ‘asking the author of a paper to name a person who did not contribute to it’ was unprofessional behavior; nevertheless, 34.7% had engaged in it. The faculty members had a less negative view of ‘admitting patients at their request despite it being medically unnecessary’ and ‘accepting a gift from a patient’ than did the residents and were more likely to have engaged in these behaviors. The residents identified ‘treating and prescribing while using another colleague’s identification to hide overtime’ as unprofessional behavior, although 25.5% had engaged in it. There was a difference for one item pertaining to perceptions of unprofessional behavior and six pertaining to experience of unprofessional behavior between the male and female respondents (Supplementary Tables 4, 5).

Unprofessional behaviors that the men had more experience with included ‘inflicting verbal or physical violence on students or juniors’ (18.3% male vs. 5.7% female) and ‘body odor arising from poor self-hygiene’ (39.2% male vs. 20.6% female). Unprofessional behaviors that the women had more experience with included ‘not deleting patient information used in a presentation from a public computer’ (51.4% female vs. 39.5% male) and ‘neglecting or gossiping about patients or their family with colleagues’ (71.4% female vs. 49.1% male).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine perceptions and experiences of unprofessional behaviors among emergency physicians and to determine whether they differed by position. Most emergency physicians were well aware of what constituted unprofessional behavior; nevertheless, many had engaged in or observed such behavior. Faculty members had more experience of unprofessional behaviors than residents.

EM residents and faculty members working at 28 university hospitals in South Korea were enrolled. Although the country-wide emergency physicians were not included, the contribution of this study is valuable because physicians working in hospitals offering residency training were enrolled, and perceptions of unprofessional behavior among senior faculty members were described. Furthermore, unlike previous studies, this survey questionnaire was administered to all EM physicians, including those in their first year of residency up to those who were faculty members [6,11,12]. This made it possible to identify differences in perceptions by position. One of the strengths of our survey was its anonymous nature, with data being collected in an automated manner rather than face-to-face so that respondents could express their opinions freely.

Despite the emphasis on professionalism in medical education, the hidden curriculum exposes residents to unprofessional behavior [13]. Instead of allowing residents to follow role models heedlessly, they should be encouraged to consider the implications and consequences of unprofessional behavior. Unprofessional behavior is strongly related to noncompliance with practice guidelines, mortality and morbidity of patients, demoralization and increasing turnover of employees, medical mistakes and adverse consequences, and lawsuits for medical malpractice. Physician leaders must act when unprofessional behavior is identified; unfortunately, there is a failure to do so because of a lack of sufficient training. Moreover, such behavior may also be emulated by others [10].

The respondents largely considered the 45 behaviors covered in our survey questionnaire as unprofessional. Nevertheless, many respondents stated that they had witnessed or engaged in such behaviors. Thus, despite being aware that certain behaviors are unprofessional, some respondents appeared unable to avoid engaging in them. This behavior of respondents can be attributed to inadequate systems within training hospitals, lack of education on professionalism, strong hierarchical structure, and poor character [14].

There were a few differences in perceptions of unprofessional behavior depending on position. Faculty members were more likely than residents to report engaging in many of the unprofessional behaviors described in the study. This likely reflects the current lack of education promoting medical professionalism. An understanding of professionalism is acquired at medical schools and by working in the field [9]. Medical staff learn about professionalism from professors when they are in school. In the field, their understanding of this concept is influenced by the behavior of colleagues, including senior staff [15]. If the teaching staff are involved in unprofessional behavior, the education aimed at promoting medical professionalism will be undermined. Developing an attitude of introspection regarding unprofessional behavior may be the first step toward obtaining a better understanding of medical professionalism.

Some previous studies demonstrated that men engage in more unprofessional behaviors than women and are more likely to justify these behaviors [11,16,17]. In this study, statistically significant difference in perception between men and women was noted for only one unprofessional behavior. This contrast in the results between our study and previous studies might have been caused by cultural differences in the background of the participants. A qualitative study through additional interviews is warranted to investigate these distinctions.

While role modeling is the most common method used to promote medical professionalism, mentoring can also aid in developing it [18-20]. However, before taking these steps, it is necessary to discuss the definition of medical professionalism and its integration in the formal/hidden curriculum [21]. Therefore, professors who teach the concept of medical professionalism should understand it fully before developing strategies for improving knowledge thereof among students [22]. Presenting examples of unprofessional behavior complements role modeling as a method for improving the understanding of medical professionalism [6]. Medical institutions and schools may be able to improve professionalism by establishing institutional norms around unprofessional behavior, teaching medical staff to recognize these behaviors, and informing staff about the consequences of violating them [10,23]. These institutions should also explore ways to address unprofessional behavior when they arise. Inclusion of medical professionalism in the standard education program of EM in South Korea would help improve the education of EM residents. This aspect may also be included as part of resident evaluation in the future. The authors suggest developing vignettes of cases regarding unprofessional behavior related to emergency care based on the results of this study. Furthermore, management of the medical professionalism curriculum for residents and faculty members by applying methods, such as ethics grand rounds and vignette-based consensus workshops, through the Korean Society of Emergency Medicine is recommended.

This study has some limitations. First, the participants included EM residents and faculty members drawn from only 28 university hospitals, and the response rate to the survey was very low. Therefore, the findings may not be representative of all emergency physicians in South Korea. In 2018, there were 1,843 EM faculty members and 630 EM residents in the country. Our sample of 253 respondents corresponds to only 10.4% of all the emergency physicians. However, to address this limitation, we included at least one university from each metropolitan council in the study. Second, our survey did not include questions regarding respondents’ experience of education in medical professionalism, which may be associated with perceptions and experiences of unprofessional behavior. Third, this study was conducted based on the 2018 survey results; therefore, there may be some differences from the current situation. The training curriculum for medical residents in South Korea is revised almost every year, which warrants periodic re-evaluation in future studies. Fourth, we did not perform additional analyses according to the faculty’s tenure. In future research, it would be good to find out how this difference influences medical professionalism. Fifth, considering several questions were described comprehensively, it is possible that there might have been differences in the understanding of and responses to the questions between respondents. Sixth, faculty staff may be more exposed to conflicting situations because the period of their clinical experience is longer than that of residents, which can result in the appearance of a higher rate of engagement in unprofessional behavior than that of residents. However, this may be because the faculty staff did not have the opportunity for self-reflection considering medical curricula and guidelines in the past were limited. Further research is needed to improve training courses aimed at promoting medical professionalism.

In conclusion, most emergency physicians were well aware of what constituted unprofessional behavior; nevertheless, many had engaged in or observed such behavior. Perceptions and experiences of unprofessional behavior among emergency physicians differed by position. Faculty members engaged in unprofessional behavior more frequently than did residents.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund and thank the emergency physicians who participated in this study.

Supplementary Materials

General characteristics of respondents (n=253)

Physician's behavior showing a significant difference in perception between residents and faculty

Physician’s behavior showing a significant difference in experience between residents and faculty

Physician's behavior showing a significant difference in perception between sex

Physician's behavior showing a significant difference in experience between sex

Overall survey results

References

Article information Continued

Notes

Capsule Summary

What is already known

Training and interest aimed at ensuring medical professionalism is lacking in residency programs in South Korea.

What is new in the current study

Most emergency physicians were well aware of what constituted unprofessional behavior; nevertheless, participants reported having experienced unprofessional behavior.