Expert opinion on evidence after the 2020 Korean Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Guidelines: a secondary publication

Article information

Abstract

Considerable evidence has been published since the 2020 Korean Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Guidelines were reported. The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) also publishes the Consensus on CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations (CoSTR) summary annually. This review provides expert opinions by reviewing the recent evidence on CPR and ILCOR treatment recommendations. The authors reviewed the CoSTR summary published by ILCOR in 2021 and 2022. PICO (patient, intervention, comparison, outcome) questions for each topic were reviewed using a systemic or scoping review methodology. Two experts were appointed for each question and reviewed the topic independently. Topics suggested by the reviewers for revision or additional description of the guidelines were discussed at a consensus conference. Forty-three questions were reviewed, including 15 on basic life support, seven on advanced life support, two on pediatric life support, 11 on neonatal life support, six on education and teams, one on first aid, and one related to COVID-19. Finally, the current Korean CPR Guideline was maintained for 28 questions, and expert opinions were suggested for 15 questions.

INTRODUCTION

The Korean cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) guidelines have been updated periodically since they were first developed in 2006, with the fourth revised version published in 2020 [1]. The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) reviews the latest evidence and publishes the Consensus on CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendation (CoSTR) every 5 years starting in 2005, which is summarized as a practice guideline. The Korean CPR guidelines can be developed based on the CoSTR because the Korean Association of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (KACPR) participated in the evidence review process as a member of the Resuscitation Council of Asia, a member organization of the ILCOR [2].

As research and publications in the field of resuscitation have increased, the need to shorten the update cycle of CPR guidelines has increased. Accordingly, the ILCOR has been conducting evidence reviews and publishing CoSTR summaries annually since 2017 [3]. It also releases an annual update of CoSTR summaries since the introduction of the 2020 guidelines [4,5], which can be found on its website (costr.ilcor.org). The Guideline Committee of KACPR concluded that it would be better to review recent evidence and to update the necessary contents before the next revision of the Korean CPR guidelines, which is scheduled for 2025. This review includes expert consensus opinions regarding the evidence on CPR published after the 2020 Korean CPR Guidelines.

EVIDENCE REVIEW METHODOLOGY

The evidence review focused on the topics of the CoSTR summaries published by the ILCOR in 2021 [4] and 2022 [5]. The members of the CPR Guidelines Committee and the evidence reviewers included experts recommended by eight professional organizations related to the CPR guidelines. The committee members and evidence reviewers were experts with experience using the methodology for revising the guidelines, including literature search, systemic review and meta-analysis, and the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) method. Members of the CPR Guidelines Committee selected items that required evidence review among the topics of CoSTR summaries. For review of the topics, the PICO (patient, intervention, comparison, outcome) format was used. For the evidence review, domestic papers as well as papers published in international journals were reviewed. PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), and KoreaMed were utilized for literature search. Since the 2020 Korean CPR Guidelines included papers published up to September 2020, papers published from October 2020 to May 2023 were included in this review. For topics not covered in the 2020 Korean CPR Guidelines, papers prior to 2020 were also reviewed. The review process used one of three methodologies: systematic review, scoping review, or evidence update. Among the PICO questions on first aid, those unrelated to CPR were excluded. A total of 43 PICO questions was selected for the review, including 15 on basic life support, seven on advanced life support, two on pediatric life support, 11 on neonatal life support, six on education implementation team, one on first aid, and one on COVID-19.

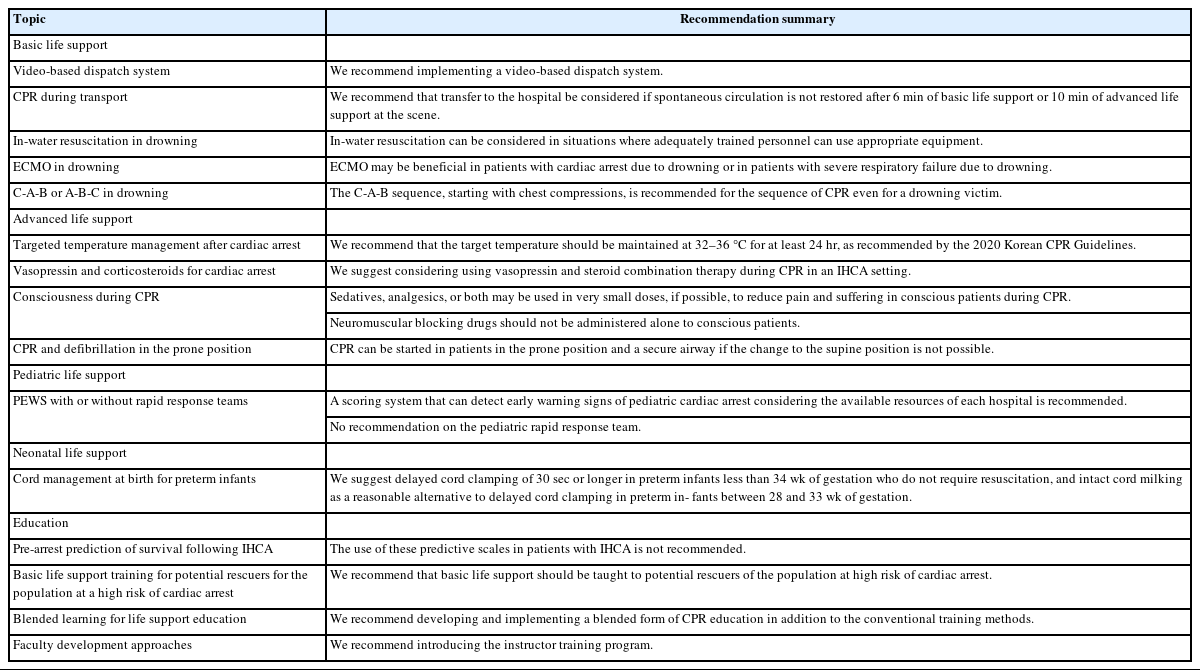

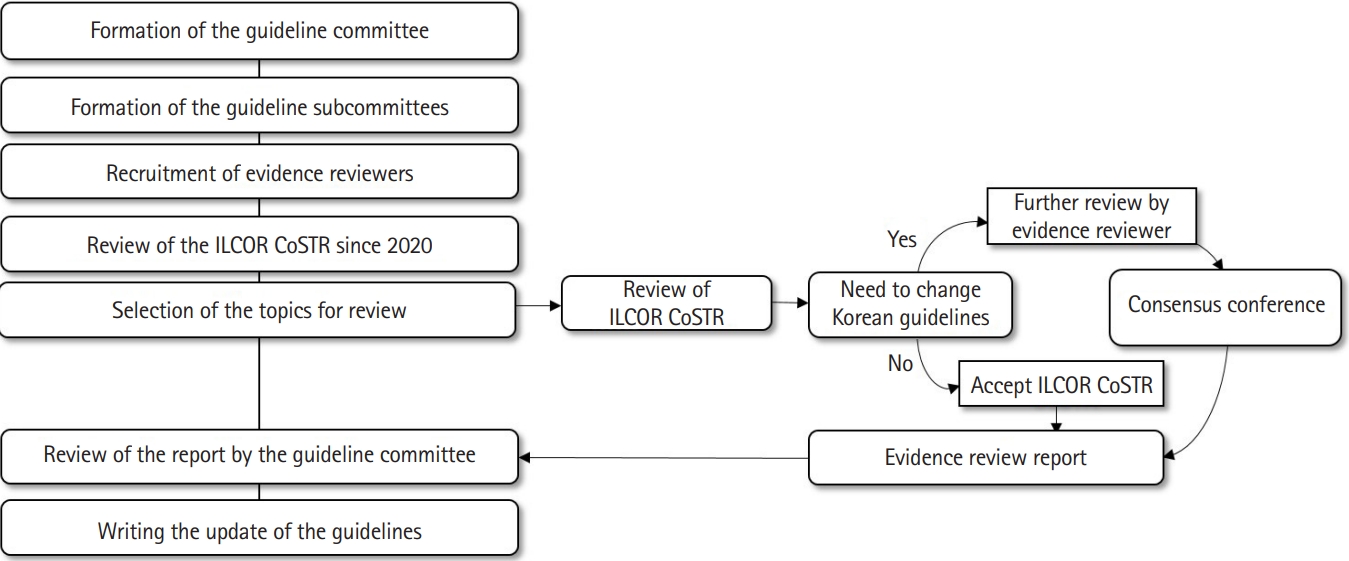

Two experts independently reviewed each PICO question. If one reviewer suggested the need for revision or addition of the 2020 Korean CPR Guidelines, the PICO question was sent to the consensus workshop for discussion and decision (Fig. 1). As a result, new expert consensus opinions were presented for 15 PICO questions (Table 1).

The process of guideline update. ILCOR, International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation; CoSTR, Consensus on CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations.

BASIC LIFE SUPPORT

Video-based dispatch system

Several studies have compared CPR quality to evaluate the effectiveness of video-based emergency dispatch systems. However, only two retrospective observational studies reported in Korea [6,7] compared patient survival as an outcome. The implementation of video-based emergency dispatch systems compared to that of the conventional audio-based systems improved the survival-to-discharge rate (22.3% vs. 10.7%; odds ratio [OR], 2.33; P<0.001) and the rate of good neurological outcomes at discharge (16.0% vs. 6.3%; OR, 2.77; P<0.001) [8]. The 2020 Korean CPR Guidelines recommend dispatcher-assisted CPR; however, only the use of speaker phones or hands-free functions is recommended during dispatcher-assisted CPR. We recommend implementing a video-based dispatch system for improving the survival rate and neurological outcomes of patients with cardiac arrest.

CPR during transport

In an observational study reported from North America [9], the intra-arrest transport group compared with the on-site CPR group had a lower survival-to-discharge rate (4.0% vs. 8.5%; risk difference, 4.6%; range, 4.0%–5.1%) and poor neurological outcomes (2.9% vs. 7.1%; risk difference, 4.2%; range, 3.5%–4.9%). However, it is difficult to generalize this result because the prehospital emergency medical services systems in North America differ from those in Korea in terms of the composition of emergency medical personnel, level of prehospital emergency care, and related legal regulations. The ILCOR suggested that CPR should be performed on-site, except in cases where the need for transport is clear, such as in cases of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) candidates.

The 2020 Korean CPR Guidelines recommend that transfer to the hospital be considered if spontaneous circulation is not restored after 6 minutes of basic life support or 10 minutes of advanced life support at the scene. For CPR during transport, the Guideline Committee decided to maintain current recommendations. During transport to a hospital, high-quality CPR should be maintained.

In-water resuscitation for individuals who experienced drowning

In a retrospective observational study [10] comparing a group that received rescue ventilation for 1 minute in water when drowning and another that did not, initial survival (94.7% vs. 37.0%, P<0.001), survival-to-discharge (87.5% vs. 25%, P=0.005), and good neurological outcome (52.6% vs. 7.4%, P=0.001) rates were higher in the group that received rescue ventilation. In-water resuscitation can be considered in situations where adequately trained personnel can use appropriate equipment.

ECMO for individuals who experienced drowning

In the 2020 Korean CPR Guidelines, there was no recommendation for the use of ECMO in individuals who experienced drowning. The ILCOR analyzed two retrospective observational studies [11,12] and 11 case reports and stated that ECMO can be considered in some patients with cardiac arrest who do not respond to conventional CPR. Therefore, ECMO may be beneficial in patients with cardiac arrest or severe respiratory failure due to drowning.

The C-A-B or A-B-C approach in cases of drowning

Nine studies were reviewed; however, none compared the order of CPR in cases of drowning [10,13,14]. The ILCOR suggested, with expert consensus, starting CPR with chest compressions (the C [circulation]-A [airway]-B [breathing] approach) for the layperson, whereas healthcare providers could consider starting rescue ventilation before chest compressions (the A-B-C approach). The 2020 Korean Guidelines do not include recommendations on whether the CPR sequence should be changed depending on circumstances, including drowning. In addition to the suggestion of ILCOR, considering the simplicity and practicality of CPR training, the C-A-B sequence, starting with chest compressions, is recommended for the sequence of CPR even for a drowning victim.

ADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT

TTM after cardiac arrest

In a targeted temperature management (TTM) trial [15] comparing target temperatures of 33 °C versus 36 °C and the TTM2 trial [16] comparing 33 °C versus normothermia below 37.5 °C (fever prevention), no difference was observed in survival to discharge, 180-day survival, or neurological outcomes at 180 days. According to a network meta-analysis [17] comparing the effects of target temperatures in 10 randomized controlled studies, compared to normothermia (37–37.8 °C), body temperatures of 31–32, 33–34, and 35–36 °C did not improve survival or neurological outcomes. The ILCOR recommended maintaining the body temperature below 37.5 °C because it can reduce the burden on medical personnel and side effects and the use of fever prevention instead of maintaining normothermia [18]. In the TTM2 study, more than 90% of the cardiac arrests were witnessed, and 62% to 63% of initial rhythms were ventricular fibrillation. The characteristics of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) patients in Korea are different from those of patients included in the TTM and TTM2 studies. Compared to patients enrolled in the TTM and TTM2 studies, Korean OHCA patients had a much lower incidence of a shockable rhythm and a longer time from collapse to recovery of spontaneous circulation, which might be associated with a higher chance of a severe post-cardiac arrest syndrome. Therefore, it is necessary to consider differences in the characteristics of cardiac arrest patients in Korea. In the fever prevention group of the TTM2 study [16], acetaminophen and a method of removing clothes and lowering the room temperature were used; temperature control devices were used to control body temperature in 46% of cases. Retrospective studies have suggested that hypothermia can improve neurological outcomes in patients with severe cerebral ischemic injury [19–21]. We recommend that target temperature should be maintained at 32–36 °C for at least 24 hours, as recommended by the 2020 Korean CPR Guidelines.

Vasopressin and corticosteroids for cardiac arrest

Three randomized controlled trials [22–24] including patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest showed that the use of vasopressin and steroids did not improve the survival to discharge rate (OR, 1.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.90–2.14) or rate of good neurological outcomes (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 0.99–2.72). However, it increased the rate of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC; OR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.54–2.84). The ILCOR recommended not using the vasopressin and steroid combination therapy during CPR because it has not been associated with any significant difference in survival, and no study including patients with OHCA has been conducted. The 2020 Korean Guidelines did not provide any recommendations on the combined use of vasopressin and steroids during CPR. Considering that the combination of these drugs increases the ROSC rate and that these drugs are commonly used in hospitals, we suggest vasopressin and steroid combination therapy during CPR in an in-hospital cardiac arrest setting.

Consciousness during CPR

There have been three observational studies; one cross-sectional study; and several case reports on pain, anxiety, agitation, and posttraumatic stress disorder in conscious patients during CPR. The studies reported that they verbally reassured the patients or administered sedatives or neuromuscular blockers [25–49]. Following the results of the scoping review conducted by the ILCOR, we recommend the following: (1) sedatives, analgesics, or both may be used in very small doses, if possible, to reduce pain and suffering in conscious patients during CPR; (2) neuromuscular blocking drugs should not be administered alone to conscious patients; (3) the optimal drug regimen for sedation and analgesia during CPR is unclear, and a regimen commonly used in critically ill patients can be used.

CPR and defibrillation in the prone position

Twenty adult and 12 pediatric cases of cardiac arrest in the prone position have been reported. Most of these cases were observed in the operating room and one case in the intensive care unit [50–68]. There was no significant difference in the rate of ROSC or survival discharge among patients for whom chest compressions were started immediately in the prone position compared with patients for which chest compressions were started after changing the position from prone to supine. Arterial pressure during CPR was higher in the prone position group [69,70]. The end-tidal carbon dioxide partial pressure in five adults and two children was 10 mmHg or higher, and the time interval from collapse to defibrillation was shortened when defibrillation was performed in the prone position [54–56,61,65,71–73]. As recommended by ILCOR, we recommend the following for adults with cardiac arrest in the prone position: (1) if cardiac arrest occurs in the prone position with a secured airway, CPR can be started if change to the supine position is not possible or poses a significant risk to the patient; (2) if cardiac arrest occurs in the prone position without a secure airway, the patient position should be changed to supine and CPR should be initiated as soon as possible; (3) if a patient with cardiac arrest is in the prone position and cannot immediately be placed in the supine position, defibrillation can be attempted in the prone position.

PEDIATRIC LIFE SUPPORT

Pediatric early warning scores and pediatric rapid response teams

One randomized controlled trial [74] and 11 cohort studies [75–85] of pediatric early warning scoring systems or implementation of a pediatric rapid response system were reviewed. The use of the pediatric early warning score tended to reduce the incidence of in-hospital cardiac arrest, mortality, and unexpected clinical deterioration. However, since research on the elements to be included in the pediatric early warning scoring system is lacking, a scoring system that can detect early warning signs of pediatric cardiac arrest, considering the available resources of each hospital, is recommended. Operation of a pediatric rapid response team is associated with a considerable decline in the preintervention trajectory of critical deterioration and a decreased likelihood of respiratory and cardiopulmonary arrest outside of the critical care unit. However, considering that the medical resources and hospital environment of the hospital where the study was conducted were different from those in Korea, the experts decided to make recommendations on the pediatric rapid response team after additional research results in Korea are released.

NEONATAL LIFE SUPPORT

Cord management at birth for preterm infants

According to a systematic review [86] comparing delayed cord clamping and early cord clamping in preterm infants with a gestational age less than 34 weeks, delayed cord clamping resulted in significantly higher hemoglobin and hematocrit within 24 hours after birth and hematocrit at 7 days after birth and lowest mean arterial pressure within 12 hours after birth. Furthermore, the risk of using inotropics due to hypotension and blood transfusions within 24 hours after birth was significantly lower in these infants. When intact cord milking and early cord clamping were compared, hemoglobin and hematocrit levels within 24 hours after birth were significantly higher and the risk of using inotropics due to hypotension and blood transfusions within 24 hours after birth was significantly lower in infants with intact cord milking. On the other hand, comparison of delayed cord clamping and intact cord milking revealed no significant intergroup differences in these parameters. Based on these findings, the 2021 ILCOR CoSTR suggests delayed cord clamping for more than 30 seconds in preterm infants less than 34 weeks of gestational age who do not require immediate resuscitation and intact cord milking as a reasonable alternative to delayed cord clamping in preterm infants between 28 and 33 weeks of gestation. The 2020 Korean CPR Guidelines recommend that umbilical cord milking not be performed in infants less than 28 weeks of gestation due to the increased risk of intraventricular hemorrhage.

We suggest delayed cord clamping of 30 seconds or longer in preterm infants less than 34 weeks of gestation who do not require resuscitation and intact cord milking as a reasonable alternative to delayed cord clamping in preterm infants between 28 and 33 weeks of gestation.

EDUCATION, IMPLEMENTATION, AND TEAM

Pre-arrest prediction of survival following in-hospital cardiac arrest

Pre-arrest clinical prediction rules, such as pre-arrest morbidity, prognosis after resuscitation, and good outcome following attempted resuscitation scores, have been studied for predicting the prognosis of patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest; however, reliable results have not been achieved [87–93]. Therefore, the use of these predictive scales in patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest is not recommended. In addition, since there have been no related studies in pediatric patients, no recommendations can be made regarding the use of prognostic predictive scales for children with in-hospital cardiac arrest.

Basic life support training for potential rescuers of populations at high risk of cardiac arrest

Potential rescuers, such as family members of high-risk patients, are less likely to voluntarily participate in CPR training but are willing to receive training [94,95]. Several studies [94–99] have recommended that basic life support be taught to potential rescuers of high-risk patients for OHCA, and that emergency staff should encourage potential rescuers to participate in basic life support. We recommend that basic life support be taught to potential rescuers of the population at high risk of cardiac arrest.

Blended learning for life support education

Blended learning is an educational method that combines face-to-face and non–face-to-face forms and was introduced in the 2020 Korean CPR Guidelines. Following the COVID-19 pandemic and the development of information technology, the use of various non–face-to-face methods has become more common in medical education [100–102]. Therefore, if resources and conditions allow, it is recommended to develop and implement a blended form of CPR education in addition to the conventional training methods.

Faculty development approach

Continuing CPR education for the public and emergency medical providers is important to increase survival rates after cardiac arrest. To provide continuous CPR training, an instructor training curriculum to teach trainees is important. Although many studies have explained the necessity of CPR instructor training programs, no study has reported that patient outcomes improved with the introduction of the instructor training program [103,104]. Nevertheless, because the instructor training program is an important factor in the teaching method and performance of trainees, it should be introduced.

CONCLUSION

The Korean CPR guidelines are revised every 5 years. Considering the situation in which new evidence continues to be published, it is necessary to update CPR guidelines to reflect the latest evidence between revision cycles. This review summarizes expert opinions based on the CoSTR summary published by the ILCOR since the publication of the 2020 Korean CPR Guidelines. We hope that this review will contribute to improving the survival of patients with cardiac arrest.

Notes

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: SOH, SPC; Methodology: SOH, SPC; Project administration: SPC; Supervision: SPC; Writing-original draft: YS, JL, YC, KCC, JSH, AREK, JGK, HSK, HS, CA, HGW, BKL, YSJ, YHC; Writing-review & editing: SOH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following members for their role in the Guideline Committee of Korean Association of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (KACPR): Do Kyun Kim (Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea), Jin Tae Kim (Seoul National University Hospital), Mi Jin Lee (Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea), Joo Young Lee (Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea), Myung Ja Cho (Republic of Korea National Red Cross, Wonju, Korea), Eun Sun Jin (Kyunghee University Hospital at Gangdong, Seoul, Korea), and Seung Tae Han (Republic of Korea Special Warfare School, Seoul, Korea).

References

Article information Continued

Notes

Capsule Summary

What is already known

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) guidelines are revised every 5 years. Since the 2020 guidelines were published, the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) has published evidence summaries every year. It is necessary to update the recommendations continuously, reflecting the new evidence.

What is new in the current study

This review summarizes the expert opinions on the new evidence since the 2020 Korean Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Guidelines. Forty-three PICO (patient, intervention, comparison, outcome) questions were reviewed, and consensus opinions were suggested for 15 questions.