Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome at the emergency department

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) is an underestimated cause of thunderclap headache that shares many characteristics with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). This fact makes the two easily confused by emergency physicians. This study evaluated the clinical manifestations, radiological features, and outcomes of patients with RCVS.

Methods

The electronic medical records of 18 patients meeting the diagnostic criteria of RCVS at our emergency department between January 2013 and December 2014 were retrospectively reviewed.

Results

The mean patient age was 50.7 years, and 80% were women. Patients with RCVS encountered physicians 4.7 times before receiving an accurate diagnosis. The mean duration of symptoms until diagnosis was 9.3 days. All but one patient experienced severe headache of 8 to 10 on a numerical rating scale. A total of 44% of patients had nausea, and 66% of patients experienced worsening of the headache while gagging, leaning forward, defecating, urinating, or having sexual intercourse. The most frequently affected vessels were the middle cerebral arteries, which demonstrated a characteristic diffuse “string of beads” appearance. Four cases were complicated by SAH.

Conclusion

Patients with RCVS have a unique set of clinical and imaging features. Emergency physicians should have a high index of suspicion for this clinical entity to improve its rate of detection in patients with thunderclap headache when there is no evidence of aneurysmal SAH.

INTRODUCTION

Headache is are classified as primary headache syndromes or headaches as a secondary effect [1-3]. Most emergency physicians focus on detecting life threatening conditions in patients with headaches [2]. As stated in the guidelines published by the American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policy for Adults with Headache in 2008, the history of the patient plays a major role in evaluation [4]. Thunderclap headache is a sudden-onset, severe headache that reaches maximal intensity within minutes. It can be associated with serious secondary etiologies that have high mortality rates, such as intracranial aneurysm, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), cervical artery dissection, and ischemic stroke [5,6]. However, the recently defined RCVS remains an underestimated cause of thunderclap headache and shares similar characteristics with SAH, particularly in terms of history [7-14]. Although the prognosis of RCVS has been reported to be generally favorable, fatal complications such as seizure, stroke, and SAH can occur a few days after diagnosis, and cerebral vasoconstriction reaches its maximum 2 to 3 weeks after clinical onset [4,7-11,15-19]. Moreover, the result in patients being subjected to unnecessary invasive testing and immunosuppressive therapy [7,13].

This study evaluated the clinical manifestations, radiological features, and the outcomes of patients with RCVS at an emergency department (ED) with the aim of enabling physicians to maintain a high index of suspicion for RCVS and thereby leading to detection in more patients with thunderclap headache by thorough history taking during initial visits when there is no evidence of aneurysmal SAH.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed the records of ED patients who presented with thunderclap headache and underwent cerebral head angiography at our medical center between January 2013 and December 2014. Before the beginning of this study, the institutional review board approved our review of patient data and waived the requirement for informed consent.

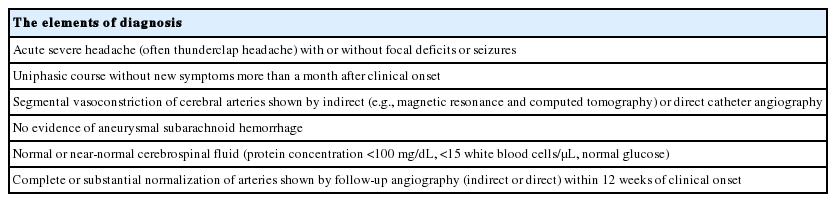

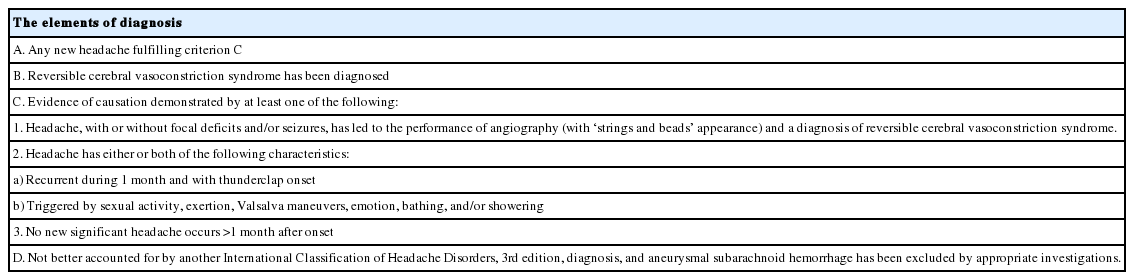

The diagnostic criteria for RCVS used in this study were based on proposed clinical, laboratory, and radiographic findings (Table 1) [8] with some recent modifications. Diagnosis of RCVS was made following the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition, 2013, for headaches attributed to RCVS (code 6.7.3) (Table 2) [1]. We excluded patients who had experienced cerebral aneurysms, cerebrovascular malformations, brain tumors, strokes, and brain hemorrhage not related to RCVS. We also excluded patients with no evidence of cerebral vasoconstriction detected by cerebral head angiography at the time of their ED visit.

To investigate the clinical manifestations, radiological features, and outcomes of RCVS, we reviewed the baseline data of patients including age, sex, medical history, headache characteristics, duration of symptoms, and relevant laboratory and imaging results. Continuous variables are expressed as means with standard deviations, or as medians and full ranges if the assumption of a normal distribution was violated. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages.

RESULTS

Clinical features

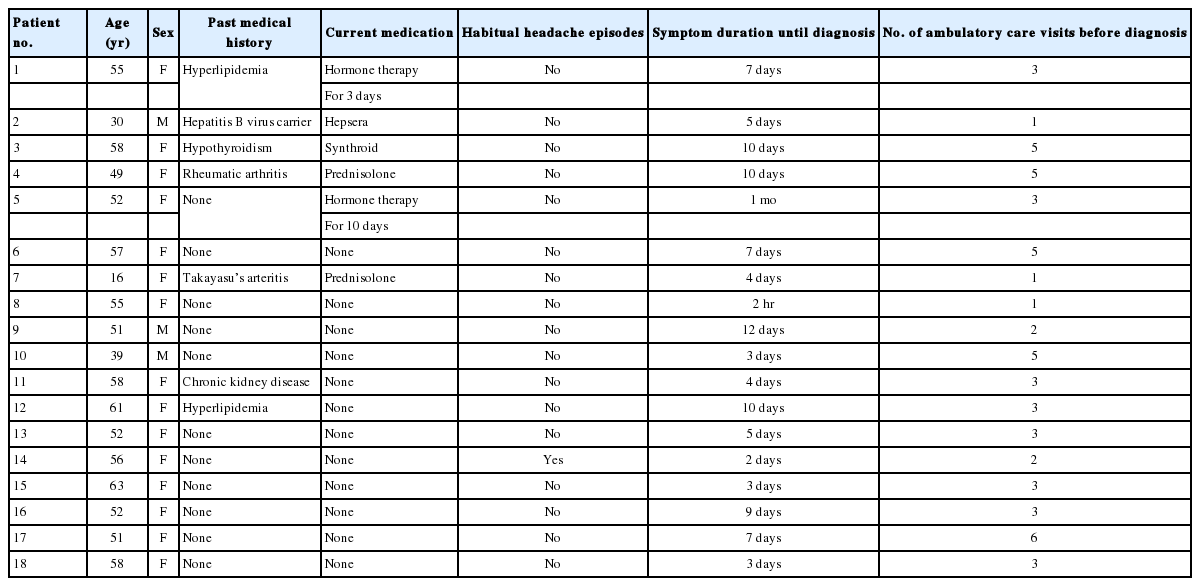

After excluding patients according to the exclusion criteria, 18 patients were diagnosed as RCVS on the basis of clinical and radiographic findings. Three patients were men; the average age was 50.7 years at the first ED visit, ranging from 16 to 63 years. Some patients had hyperlipidemia, one had chronic hepatitis B virus infection, one had chronic kidney disease, and one had hypothyroidism. Two patients were taking steroids because of Takayasu’s arteritis and rheumatic arthritis. Two patients were taking hormonal agents, but both of them started taking the pills to relieve their pain after their severe headaches began. Before an accurate diagnosis, their headaches were misdiagnosed as postmenopausal symptoms. Other than these seven patients, 11 patients did not have any past medical histories. Only one patient had habitual headache episodes and the other 17 patients reported never experiencing headaches in their lifetime (Table 3). We reviewed the study population for the conditions associated with RCVS, such as pregnancy-related conditions (late pregnancy, early puerperium, pre-eclampsia, and eclampsia); blood product transfusion; surgical procedures; and exposure to various vasoactive medications such as oral contraceptive pills, hormonal agents, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, alpha-sympathomimetic decongestants, illicit drugs, and acute migraine medications were reviewed, but no patients reported having these conditions or taking such medications. The mean duration of symptoms until diagnosis was 9.3 days, ranging from 2 hours to 1 month. The average number of ambulatory care visits before diagnosis was 4.7, ranging from 1 to 6.

Headache profiles

Four patients reported a headache in the middle of the vertex, four in the occipital area, three in the frontal area, and seven over the entire head. Six patients described pulsating headaches, and 11 reported explosive headaches. Seventeen patients, excluding one who reported a pain intensity of 6, experienced severe headaches (pain intensities of 8 to 10 on a numerical rating scale). All patients reported sudden severe headaches that reached maximum intensity within minutes and were sustained for 30 minutes to several hours with residual moderate headaches between the severe exacerbations. Painkillers reduced the intensity of pain but did not eliminate it completely. Patients had to take painkillers over time because the headaches were not relieved easily with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen. No patient had aura preceding the headache attacks. Nausea and vomiting were reported at the onset of headache in seven patients. Eleven patients reported that strenuous exercise, sexual activity, coughing, defecating, urinating, gagging, or other Valsalva triggering maneuvers exacerbated the headaches. Identified triggering factors in our study were tooth brushing, drinking beer, eating wasabi, swimming, and exposure to cold weather. Even though no patients had a history of hypertension, 15 patients had acute blood pressure elevation during triage, which may have been secondary to pain (Table 4).

Radiographic findings and clinical course

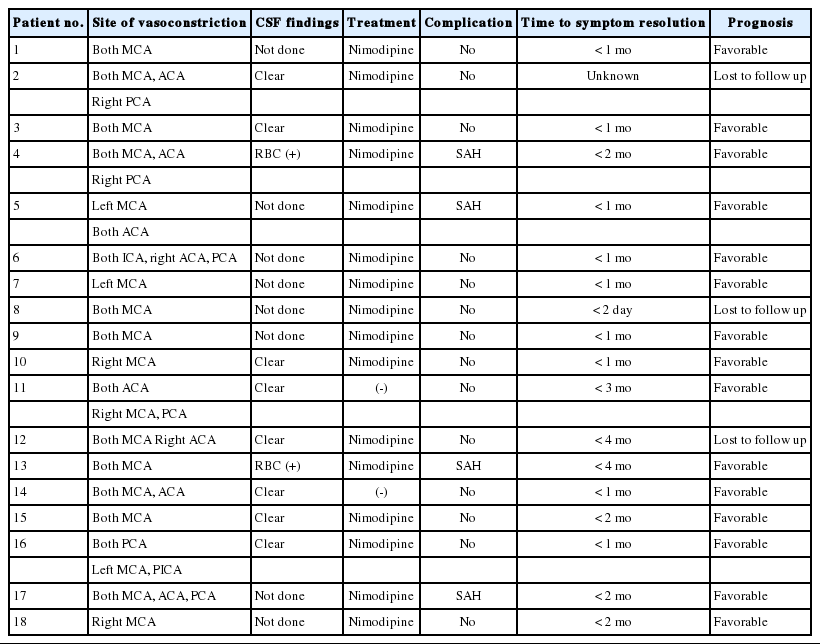

Focal neurological deficits and seizures were not observed in any patients. The most frequently affected vessels were the middle cerebral arteries. Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the brain performed in 17 patients demonstrated the characteristic diffuse “string of beads” appearance in the middle cerebral arteries (Figs. 1, 2). The anterior circulation was affected in nine patients and the posterior circulation in six. In 15 patients (except patients 1, 2, and 18), ancillary serum laboratory investigations were performed, including blood count, electrolyte levels, hepatic and renal function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein level, antinuclear and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and rheumatoid factor to exclude underlying connective tissue disorders such as infectious arteritis and inflammatory vasculitis, which share the radiological findings of RCVS. Patients 4, 6, and 11 were positive for rheumatoid factors. Their follow up CT angiography on days 20, 12, and 18 demonstrated complete resolution of vasoconstriction. The time to resolution of symptom ranged from 2 days to 4 months, but most patients reported that their headache was resolved within 2 months. All patients were given analgesic medications and bed rest. Nimodipine was administered to 16 patients due to its anti-vasospastic properties. Patients 11 and 14 were not given nimodipine. The blood pressure of these two patients was too low to start calcium channel blocker therapy. All patients reported a monophasic course without new headaches after the clinical diagnosis of RCVS was made. Other than three patients who were lost to follow-up, 15 patients had neither neurologic sequelae nor chronic headaches (Table 5).

A computed tomography angiography image of patient 17 on day 7 showing multifocal arterial narrowing of the cerebral arteries.

A transfemoral cerebral angiography image of patient 17 showing multifocal arterial narrowing of the cerebral arteries.

DISCUSSION

RCVS is characterized by acute, severe headaches with or without additional neurological deficits, often triggered by sexual activity, exertion, Valsalva maneuvers, emotion, and constriction of the cerebral arteries that resolves spontaneously within 12 weeks [1,7,10,11,13,20-22]. The diagnostic criteria are based on clinical, laboratory, and radiographic findings (Table 1) [1] and have been modified recently (Table 2) [1,7,15].

The exact incidence of RCVS is unknown, but it does not seem to be especially rare [7,13]. Its incidence is estimated to be between 8.8% and 45.8% in patients with thunderclap headache and those without an obvious secondary cause of headache [12,23]. However, it might be underestimated because there is no research reporting the incidence of RCVS in ED patients, the most common mode of entry for patients presenting with thunderclap headache.

The characteristics of headaches associated with RCVS are severe pain that peaks in minutes, causing screaming, crying, agitation, and even collapse. For these reasons, it can often be confused with a ruptured aneurysm [24,25]. Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia frequently accompany the headaches [8,10,11,23-27]. The headache is mostly moderate in severity between exacerbations [7]. Headaches caused by RCVS are not relieved easily with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen, which are the initial recommendations for primary headaches. This causes patients to repeatedly visit doctors seeking relief from the severe pain. In our study, patients with RCVS visited an average of 4.7 physicians before receiving an accurate diagnosis.

In one study by Ducros et al. [26], vasoconstriction was detected at a mean of 8 days after headache onset, and up to 14 days in some patients. According to the present study, the mean duration of symptoms until diagnosis was 9.3 days. The results reveal that the incidence of RCVS is significantly underestimated and highlight the need for emergency physicians to be aware of RCVS in patients with severe-onset headaches.

Cerebral head angiography is essential for diagnosing RCVS [14]. CT angiography images of our patients showed multifocal segmental narrowing and dilatation of the cerebral arteries. Follow-up CT angiography showed complete regression of vasoconstriction.

The present study was limited by its retrospective nature, the small number of patients included, and the lack of a control group. Further study will be needed to evaluate the treatment of RCVS.

ED physicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for RCVS in order to improve its detection rates in patients with thunderclap headache when there is no evidence of aneurysmal SAH, not only because of its relatively high incidence and clinical manifestation of severe headache, but also because of the easy accessibility of newer, relatively noninvasive technologies such as CT angiography and magnetic resonance angiography to assess the cerebral vasculature. Furthermore, early recognition is important so that symptoms can be managed effectively with the elimination of precipitating factors and unfavorable complications such as seizure, stroke, and SAH.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

Article information Continued

Notes

Capsule Summary

What is already known

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome remains an under recognized cause of thunderclap headache that shares a similar history with subarachnoid hemorrhage.

What is new in the current study

This study evaluated the clinical manifestations, radiological features, and outcomes of patients with reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. It also focused on the average number of visits to the physicians before an accurate diagnosis and the mean duration of symptoms until diagnosis revealing a significant under recognition of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome.