AbstractObjectiveAcute gallbladder disease (AGD) is frequent in the emergency department (ED) and usually requires emergency surgery. However, only a few studies have reported the impact of COVID-19 on AGD. The goal of this study was to evaluate the time between symptom onset and surgery and the perioperative severity of AGD during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the era of COVID-19.

MethodsThis retrospective, single-center cohort study included patients who presented to the ED with suspected AGD and who underwent emergency cholecystectomy. We designed a before-after comparative study, and the intervention was the COVID-19 outbreak. The 6-month period after the COVID-19 outbreak was defined as the post-COVID group, whereas the pre-COVID group consisted of the same period in the previous year. The primary outcome was the time from symptoms to surgery. We evaluated the time intervals between symptom onset and ED arrival and between ED arrival and surgery. The secondary outcomes were preoperative and postoperative severity indexes.

ResultsA total of 316 patients was analyzed. The post-COVID group showed longer duration from symptom onset to ED arrival (34.0 hours vs. 15.0 hours, P<0.001) and longer time interval from ED arrival to surgery (16.2 hours vs. 10.2 hours, P<0.001) than the pre-COVID group. The overall time interval between symptom onset to surgery was longer in the post-COVID group than the pre-COVID group (71.5 hours vs. 33.5 hours, P<0.001). The post-COVID group showed higher preoperative Simplified Acute Physiology Score II scores than the pre-COVID group (20.1 vs. 18.2, P=0.045). The proportion of moderate or severe disease increased in the post-COVID group (78% vs. 65%, P=0.017). The durations of hospital stay (7.0 days vs. 5.0 days, P<0.001) and intensive care unit stay (27.1 hours vs. 10.8 hours, P=0.008) were longer in the post-COVID group than in the pre-COVID group.

INTRODUCTIONAcute gallbladder disease (AGD) is a common clinical issue among patients who visit the emergency department (ED). Acute cholecystitis (AC) with gallstones is the most frequent presentation of AGD and can manifest as inflammation without gallstones or colic pain without inflammation [1]. The diagnosis and management plans for this disease are well established [2-4]. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is recommended in AC, and percutaneous drainage of the gallbladder or medical treatment offers alternative options [5]. Delay in proper management may lead to unfavorable outcomes for patients with AGD.

The unexpected spread of novel coronavirus infection has significantly affected healthcare worldwide. After the COVID-19 outbreak, global ED visits drastically decreased and did not return to the level before the pandemic for more than 6 months [6-12]. Furthermore, the number of ED visits with critical and emergent illnesses concomitantly decreased [9,12]. Deferring necessary care and avoiding visiting healthcare facilities were reported as potential causes of these decreases [11-13].

Several studies have reported the impact of COVID-19 on AGD worldwide. According to the position statement by the World Society of Emergency Surgery, LC remains the treatment of choice for AC in the era of COVID-19 [14]. Furthermore, LC is indicated in COVID-19-positive patients for which medical treatment or interventional management is ineffective [15]. A study has reported the challenges and dilemmas in AC management during the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore; however, the study was limited to opinions of surgeons by survey without clinical outcomes [16]. Studies from the United States and Ireland have shown a reduced number of AC cases during the pandemic and have discussed the severity of the disease [17,18]. Thus, we designed a study to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on patients with AGD who visited an emergency room (ER) and underwent emergency cholecystectomy in Korea. The goal of this study was to evaluate the time between symptom onset and surgery and the perioperative severity of AGD during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before the era of COVID-19. We analyzed the integrated current clinical aspects of particular gallbladder diseases under pandemic situations from an Asian perspective because Asia was the region of origin for the novel coronavirus outbreak.

METHODSWe designed a before and after comparative study on patients with AGD undergoing emergency cholecystectomy. The retrospective cohort study was conducted at an academic teaching hospital (CHA University Gumi Medical Center, Gumi, Korea). This secondary referral center is a level 1 regional ED in Korea, and the annual number of emergency cholecystectomies at the institution ranges from 300 to 350 [19]. Patients who were managed during the 6-month period after the COVID-19 outbreak from March 1 to August 31, 2020, were defined as the post-COVID group, whereas the pre-COVID group consisted of patients who were managed during the same period in the previous year from March 1 to August 31, 2019. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of CHA Gumi Medical Center (No. GM21-04), and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

We collected data from the medical records of patients who visited the ED with a clinical presentation of AGD and those who were suspected to have AGD upon ED evaluation. We defined AGD as follows: (1) clinical manifestation such as right upper quadrant or upper abdominal colic pain and history of fever or (2) acute inflammation of the gallbladder, presence of gallstones, or other abnormal findings of the gallbladder on ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT). The attending emergency physician and the senior hepato-pancreato-biliary surgeon made the decision regarding surgery. We excluded patients with incomplete data, those who refused to undergo surgery, and those who were managed by percutaneous drainage first and underwent delayed cholecystectomy afterward.

Demographic and clinical data were age, sex, vital signs and mental status upon ED arrival, severity of pain, and duration of symptoms before ED arrival. Moreover, we obtained the results of preoperative laboratory and radiological evaluations at the ED, the interval between ED arrival and surgery, duration of surgery, the results of pathological evaluations, total duration of hospital stay after surgery, duration of intensive care unit (ICU) stay, the occurrence of readmission within 30 days after discharge, and inhospital mortality.

We measured the severity of pain using a numerical rating scale, which is a simple popular tool in the ED [20]. Individual patients rated their pain from 0 to 10 upon ED arrival, with a score of 0 indicating “absolutely no pain” and a score of 10 representing “the worst imaginable pain.” To estimate the disease severity of each patient, the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II, and quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) were used. The qSOFA score was rated positive when two or three criteria were fulfilled. Preoperative diagnosis and severity grading of AC were determined according to the Tokyo Guidelines 2018 (TG18) [2]. All the severity factors were measured and calculated based on clinical information and preoperative evaluation at the ED, except urine output, which was measured for 8 hours after ED arrival throughout the hospital stay. The pathologist confirmed the final diagnosis after cholecystectomy.

We presented categorical variables as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were reported as means±standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges. The normality of the data was evaluated using skewness and kurtosis analyses and the Shapiro-Wilk test. The chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. A t-test was used to compare normally distributed continuous variables, and non-normally distributed data were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U-test. All tests were two-tailed, and P-values less than 0.05 were used to indicate statistical significance. Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS ver. 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

The primary outcome of interest was the time from symptom onset to surgery. We evaluated the time intervals between symptom onset and ED arrival and between ED arrival and surgery. The secondary outcome was the perioperative severity index. We compared postoperative factors of length of in-hospital stay, total accumulated duration of ICU stay, in-hospital mortality, and results of the pathological examinations between the groups.

RESULTSGeneral descriptionIn total, 358 patients presented to the ED with suspicion of AGD during the previously mentioned periods. After excluding 42 patients according to the exclusion criteria, 316 who underwent emergency cholecystectomy for AGD were included for analysis (Fig. 1). Demographic and preoperative clinical data are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences in age and sex were observed between groups (P=0.355 and P=0.196, respectively).

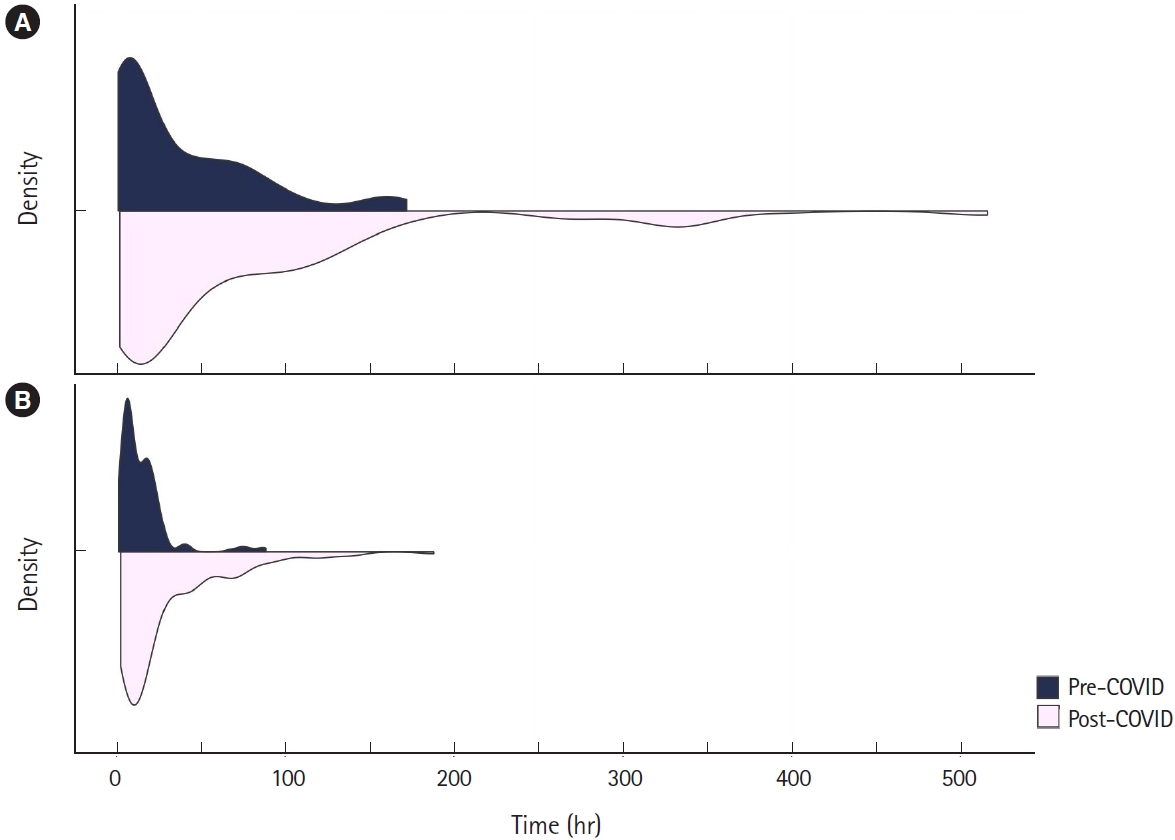

Primary outcomesThe duration of symptoms before ED arrival was significantly longer in the post-COVID group than in the pre-COVID group (34.0 hours [range, 9.0–98.5] vs. 15.0 hours [range, 5.0–66.0], P<0.001) (Fig. 2). The post-COVID group showed a significantly longer time interval between ED arrival and surgery than the pre-COVID group (16.2 hours [range, 7.7–43.2] vs. 10.2 hours [range, 6.3–19.5], P<0.001) (Fig. 2).

Secondary outcomesOn analysis of clinical severity estimation, the post-COVID group showed higher SAPS II and APACHE II scores than the pre-COVID group. However, only differences in SAPS II scores were statistically significant (20.1±8.9 vs. 18.2±7.7, P=0.045) (Table 2). Severity grading using the TG18 criteria showed relevant differences between the groups. The proportion of patients with moderate or severe disease (TG18 grade II or III) significantly increased in the post-COVID group relative to the pre-COVID group (52.3% vs. 38.9%, P=0.017).

The mean operation time was not statistically different between the two groups (P=0.414). The total duration of hospital stay and the mean duration of ICU stay were longer in the post-COVID group than in the pre-COVID group with significant differences (7 days [range, 5–10] vs. 5 days [range, 4–7], P<0.001; 27.1±69.2 hours vs. 10.8±36.6 hours, P=0.008, respectively). Although the number of patients admitted to the ICU, those who were readmitted within 30 days after discharge, and in-hospital mortality was not significantly different between the two groups.

Up to 90% of the patients had AC on the pathological evaluation, and acute calculus cholecystitis was the most common clinical condition in both groups (64.4% and 63.5%, respectively). The post-COVID group had a trend of a higher proportion of complicated AC (such as acute suppurative cholecystitis or acute gangrenous cholecystitis) than the pre-COVID group (23.5% vs. 20.4%), but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (P=0.501) (Table 3). In addition to AC, chronic calculus cholecystitis, cholelithiasis without inflammation, and gallbladder malignancy were reported.

DISCUSSIONIn this study, we found that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected particular surgical emergencies associated with AGD. The overall time interval between symptom onset to surgery was longer during the pandemic. In addition, the duration of symptoms before ED arrival was significantly prolonged, and there was a remarkable delay in emergency surgery. Secondarily, several perioperative indexes including severity scores and grading and length of hospital stay were poor during the pandemic.

Needless to say, a shorter time interval between symptom onset and ED arrival is associated with a better prognosis in numerous critical disease entities, such as acute coronary syndrome and cerebrovascular accidents [13]. Similarly, prolonged complaint duration is a major component of severity grading using the TG18 in AC. One study has suggested a relationship between longer symptom duration and surgical outcomes of AGD during the COVID-19 pandemic [21]. We postulate that delayed ED presentations of the post-COVID group were causally related to the higher TG grades and poorer severity scores in this study. The public tendency to postpone emergency care or the shutdown of EDs, which were discussed as factors for the decline in the number of ED visits, potentially affected these trends of delay [8,12,22]. Furthermore, the limited prehospital emergency care resources during a pandemic is another considerable factor. One regional study reported shortage of emergency medical services and subsequent delays in transport of patients with severe illnesses [23].

Longer ED stays have been reported worldwide during the COVID-19 pandemic [23,24]. Various mandatory preoperative steps were added at the ED. The World Society of Emergency Surgery recommended performing tests for COVID-19 infection at the ED for all emergency surgical patients [25]. Additional chest CT should be performed in patients who underwent abdominal CT [26]. To ensure surgical team safety, organizing an operating room to be COVID-19-protected requires more time. As a result, several inevitable delays occurred before surgery in this study. The guidelines recommend that early LC be performed as soon as possible to achieve better outcomes in AC [4]. In this study, we observed poor clinical effects, such as lengthened total duration of hospital and ICU stays in the post-COVID group. Furthermore, a larger proportion of complicated AC was possibly associated with those periods between the groups. Consequently, the prolonged interval between ER arrival and surgery, in conjunction with delayed ED presentation, may have contributed to worse surgical outcomes.

The operative duration should be considered in the era of COVID-19, although no statistical significance was observed in this study. Surgical smoke, which contains toxic components, is frequently produced during abdominal surgery. Still, there is no clear evidence to indicate the presence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in surgical smoke; in contrast, viral RNA has been detected in peritoneal fluid [14]. However, a considerable risk of infection remains for the surgical team, especially during laparoscopic surgery. The guidelines recommend equipping the necessary personal protective equipment for the surgical staff [25]. Using ultra-low particulate air filters in the operating room may be effective [14]. Proper protocols for the entire operative management should be established to perform a safe surgical procedure [25]. To ensure the specific safety precautions, a longer operative duration is necessary before the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Substantially longer operative duration is associated with a higher risk of complications, and we should consider the potential negative effect of prolonged operative time in the post-COVID group [27].

Although 2 years have passed since the original outbreak, we have not entirely overcome the global crisis. Furthermore, we are threatened by potential dangers, such as novel viral variants. As outlined in this study, the pandemic has critically affected the system of emergency medicine, as well as the particular urgent surgical entity. Future strategies should be discussed to minimize the risk of COVID transmission. A rapid transition to COVID-19-specific EDs can be a proactive solution to the limited emergency care resources [28]. Against the fear of hospital-acquired infection of the public, ED staff should exert necessary efforts to assure safety with pertinent preventive protocols [7]. Regardless of the specific conditions, appropriate emergency care is key for global health.

This study has obvious limitations. First, the retrospective study design is limited in helping us understand the current situations. A mixed-methods study will be needed, including a survey on patient health care use like avoidance or hesitancy to seek care. A prospective design should be considered in future studies. Second, collected from a single institution, the data may not represent the entire nation. Thus, the results should be interpreted cautiously. The duration of symptoms varied by patient. As time passed for days or weeks after the onset, it became difficult to remember and express the exact time. The low accuracy of particular time factors could be an additional limitation. Other limitations included the absence of COVID-19-positive patients in this study. As the institution has been designated to care for COVID-19-positive patients since 2021, we could not conduct an integrated analysis between COVID-19 and AGD.

In conclusion, during the pandemic, the time interval between symptom onset to surgery was significantly increased among patients with AGD. Concomitantly, poor preoperative severity indexes and longer hospital stay were reported with a sequential delay in emergency surgery.

REFERENCES1. Lam R, Zakko A, Petrov JC, Kumar P, Duffy AJ, Muniraj T. Gallbladder disorders: a comprehensive review. Dis Mon 2021; 67:101130.

2. Yokoe M, Hata J, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2018; 25:41-54.

3. Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2018; 25:55-72.

4. Pisano M, Allievi N, Gurusamy K, et al. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg 2020; 15:61.

5. Baron TH, Grimm IS, Swanstrom LL. Interventional approaches to gallbladder disease. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:357-65.

6. Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits: United States, January 1, 2019-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:699-704.

7. Venkatesh AK, Janke AT, Shu-Xia L, et al. Emergency department utilization for emergency conditions during COVID-19. Ann Emerg Med 2021; 78:84-91.

8. Eurick-Bering K, Chowdhury N, Hjaige M, Kenerson R, Revere T, Reece RJ. 85 Impact of COVID-19 on patient populations in the emergency department in Flint, Michigan. Ann Emerg Med 2021; 78:S39-40.

9. Walker LE, Heaton HA, Monroe RJ, et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on emergency department presentations in an integrated health system. Mayo Clin Proc 2020; 95:2395-407.

10. Gutovitz S, Pangia J, Finer A, Rymer K, Johnson D. Emergency department utilization and patient outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in America. J Emerg Med 2021; 60:798-806.

11. Lee DD, Jung H, Lou W, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on a large, Canadian community emergency department. West J Emerg Med 2021; 22:572-9.

12. Kim HS, Cruz DS, Conrardy MJ, et al. Emergency department visits for serious diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Emerg Med 2020; 27:910-3.

13. Chang H, Yu JY, Yoon SY, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the overall diagnostic and therapeutic process for patients of emergency department and those with acute cerebro-vascular disease. J Clin Med 2020; 9:3842.

14. Campanile FC, Podda M, Arezzo A, et al. Acute cholecystitis during COVID-19 pandemic: a multisocietary position statement. World J Emerg Surg 2020; 15:38.

15. Arezzo A, Francis N, Mintz Y, et al. EAES recommendations for recovery plan in minimally invasive surgery amid COVID-19 pandemic. Surg Endosc 2021; 35:1-17.

16. Chia CL, Oh HB, Kabir T, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on management of acute cholecystitis in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap 2020; 49:817-24.

17. Valles KF, Neufeld MY, Caron E, Sanchez SE, Brahmbhatt TS. COVID-19 pandemic and the cholecystitis experience at a major urban safety-net hospital. J Surg Res 2021; 264:117-23.

18. Kamil AM, Davey MG, Marzouk F, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on emergency surgical presentations in a university teaching hospital. Ir J Med Sci 2022; 191:1059-65.

19. Nho WY, Kim JK, Kee SK. A comparative analysis of gallbladder torsion and acute gallbladder disease without torsion: a single-center retrospective case series study. Ann Transl Med 2021; 9:1399.

20. Karcioglu O, Topacoglu H, Dikme O, Dikme O. A systematic review of the pain scales in adults: which to use? Am J Emerg Med 2018; 36:707-14.

21. Farber ON, Gomez GI, Titan AL, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on presentation, management, and outcomes of acute care surgery for gallbladder disease and acute appendicitis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13:859-70.

22. Kim D, Jung W, Yu JY, et al. Effect of fever or respiratory symptoms on leaving without being seen during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2022; 9:1-9.

23. Kim HS, Jang TC, Kim GM, Lee SH, Ko SH, Seo YW. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak on the transportation of patients requiring emergency care. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99:e23446.

24. Chun SY, Kim HJ, Kim HB. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the length of stay and outcomes in the emergency department. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2022; 9:128-33.

25. De Simone B, Chouillard E, Sartelli M, et al. The management of surgical patients in the emergency setting during COVID-19 pandemic: the WSES position paper. World J Emerg Surg 2021; 16:14.

26. Moletta L, Pierobon ES, Capovilla G, et al. International guidelines and recommendations for surgery during Covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Surg 2020; 79:180-8.

Fig. 2.Density plot of the primary outcomes. The time interval factors were compared between the groups. (A) From symptom onset to emergency department (ED) arrival. (B) From ED arrival to surgery.

Table 1.Demographic characteristics and preoperative clinical summary of the study participants

Values are presented as median (interquartile range), number (%), or mean±standard deviation. ED, emergency department; SpO2, saturation of percutaneous oxygen. a) Patients who were managed during the 6-month period before the COVID-19 outbreak, from March 1 to August 31, 2019. Table 2.Primary and secondary outcomes of the study

Values are presented as median (interquartile range), mean±standard deviation, or number (%). ED, emergency department; SAPS, Simplified Acute Physiology Score; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; qSOFA, quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment. Table 3.Final pathological diagnoses of patients with acute gallbladder disease

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||